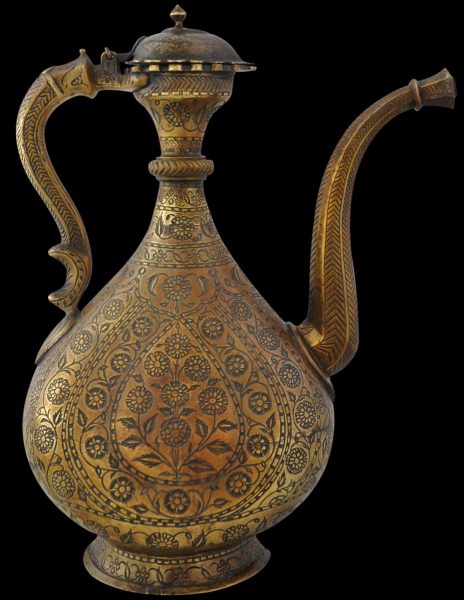

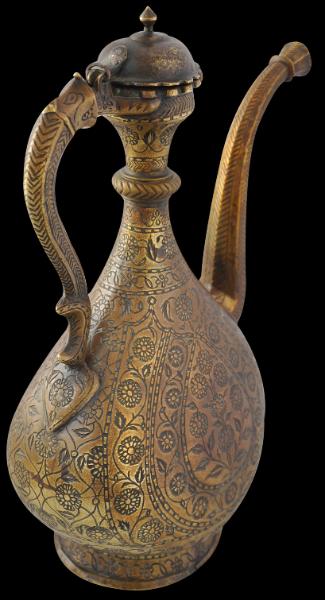

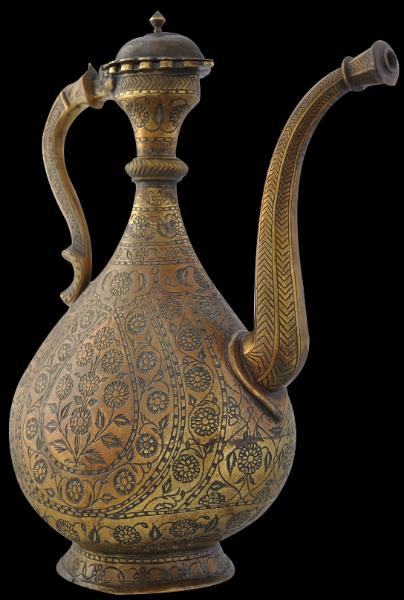

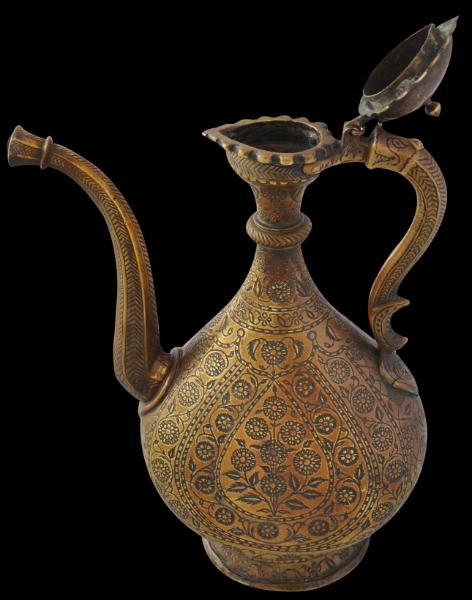

This magnificent and highly decorative Mughal brass ewer (aftaba) is of impressive size and refined proportions. It is in excellent condition for its age, has a warm, golden patina.

It stands on a flared, oval foot which rises to a tear-shaped body with rounded contours and softly tapering sides. The neck flares slightly to the tear-shaped opening with a serrated-edged rim. A domed lid sits in the mouth. The lid, itself with a fine patina, is a later but early replacement. (More often than not, ewers from this period are missing their lids altogether.)

The handle is of ‘S’ shaped form. The top of the handle is engraved both sides with a stylised makara face, thereby suggesting a dragon or makara form for the handle. The handle is engraved with bands of zig-zag motifs.

The spout of tapering pentagonal form also has a gentle ‘S’ shape which leads to a flared head. It too is decorated with engraved zig-zag bands.

The body is engraved on all sides with cartouches and borders of stylised poppy motifs and borders of carnations or pinks identifiable by their serrated petals. The engraving on the body is bordered at the top by a series of Sino-Persian stylised cloud cusps not unlike the decoration found on early export Chinese porcelain ewers and the like made for export to Persia. More floral borders are engraved above these. The stylisation evident in the poppy and carnation motifs clearly follows the motifs used in Ottoman tiles and other works of porcelain.

The engraving is highlighted with dark lac.

The base of hammered brass sheet is original and is folded and hammered over the foot to keep it secure.

Typical Islamic ewers comprised a central chamber to which a spout, foot, handle and neck were attached. They permitted water to flow – Koranic injunctions deemed flowing water to be ‘clean’. Ewers were introduced to India by Muslim invaders during the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. Thereafter their designs were Indianised – the ewers became more curvaceous and were decorated with lush plant and floral motifs.

In India, local Muslims used such vessels for handwashing. They became a practical tool of hospitality, being used to welcome visitors by pouring scented water over the hands and feet and into a basin. In this way, the motifs employed on such vessels in Northern India can be seen as particularly appropriate: the scrolling arabesques and trellised cartouches of floral sprays can be seen as representative of a paradisical garden, a destination of pleasure and balm – the orderly, repeated pattern of floral cartouches can be seen as representing the ordered layout of the idealised Islamic garden (Thomas, 2011).

The zig-zag patterns on the neck, handle and spout convey a sense of flowing water, both in terms of the ‘streams’ which one would expect to find in a Mughal garden, and, by dint of both the direction of travel – away from the handle and down the spout – and with the curvature of both of these features of the ewer, a sense of movement is achieved which would be lacking in a strictly repeated foliate design (Thomas, 2011.) Or perhaps they suggest the scales of a cobra, a stylistic device often encountered in Mughal, Deccan and other Islamic architecture in northern India to decorate columns and even guttering.

North Indian ewers of this quality have become increasingly scarce and are much sought after. This was particularly evidenced by the prices achieved for better quality Mughal ewers in the Christie’s and Sotheby’s sales of the collections of Stuart Carey Welch and Simon Digby in London in April 2011. This example is an especially fine example, with marvellous form and presence.

Water or perhaps snake skin motifs in marble on the Taj Mahal, Agra, India.

Detail on a column at Fatehpur Sakti, the Mughal capial founded in 1571 and which predates Delhi.

The underside of the central basin of this marble fountain in a courtyard of the ninth century and later Nasrid Palaces, Granada, Andalucian Spain, shows a similar repeated zig-zag water flow motif. (Photographed in October 2011.)

References

Dye, J.M., The Arts of India: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Philip Wilson Publishers, 2001.

Thomas, D., ‘The carnation ewer – an example of Ottoman influence on North Indian ewers’, unpublished paper, 2011.

Zebrowski, M., Gold, Silver & Bronze from Mughal India, Alexandria Press, 1997.