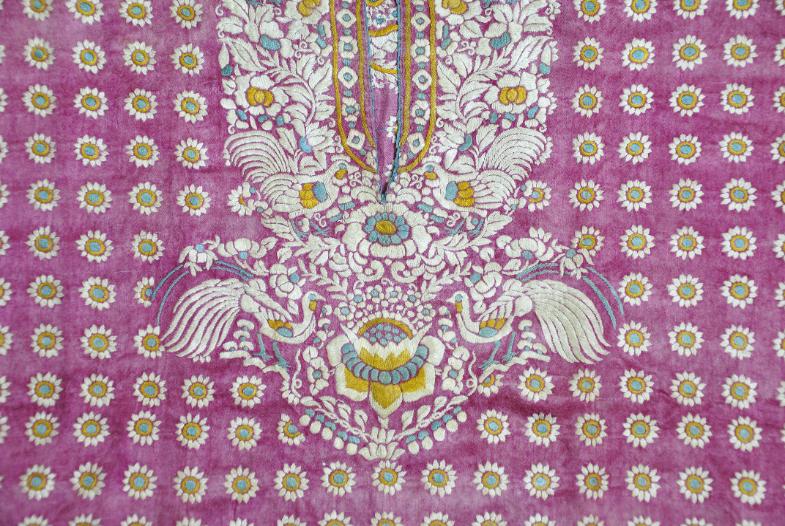

Parsee Parsi Embroidered Vest

Embroidered Vest

Parsi (Parsee) People, Gujarat, Northern India

early 19th century

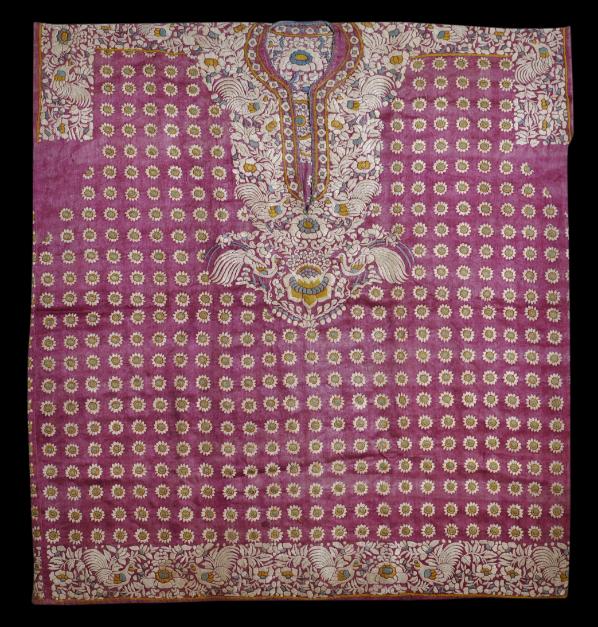

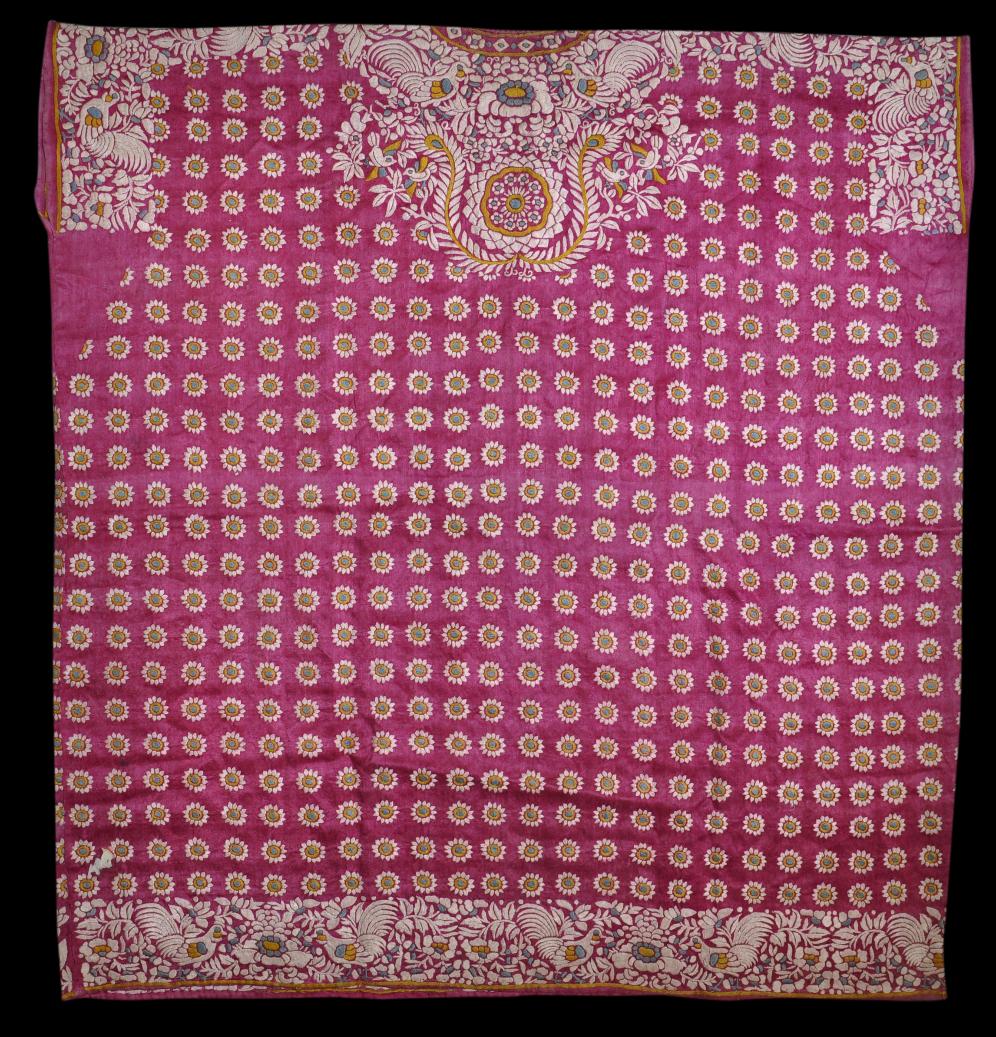

height: 56cm, width: 51cm

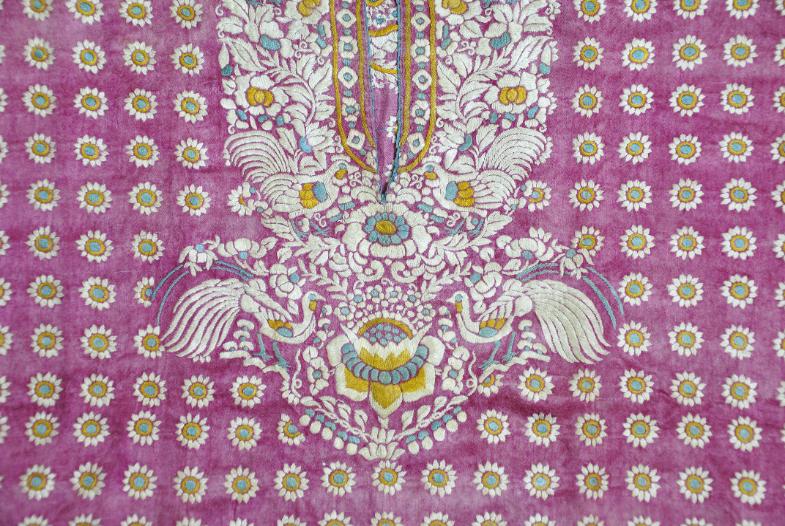

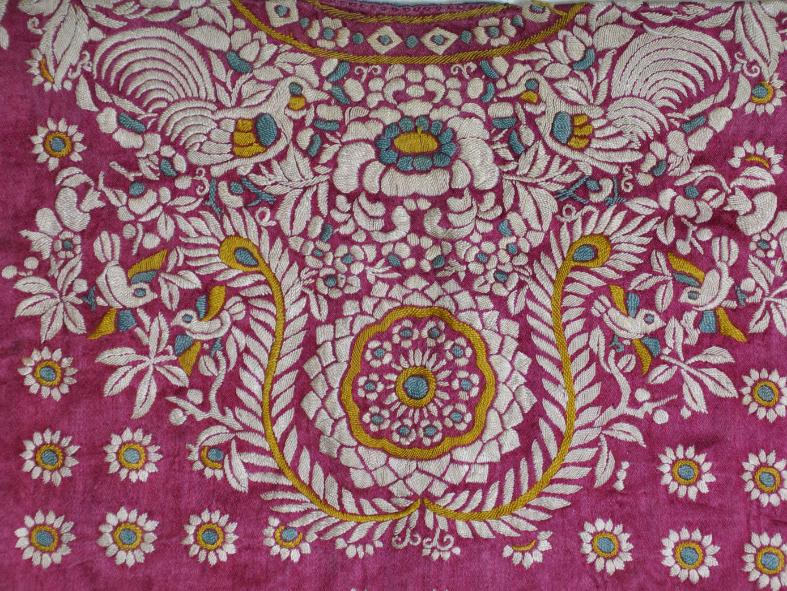

This red silk vest known as a jhabla, worn by a Parsee of Gujarat in Western India, is elaborately embroidered in cream, yellow and green thread on both sides. Ostensibly Chinese in style, it is a locally-made copy of a Chinese embroidered item. Parsee embroideries were very popular among the Parsee community of India during the nineteenth century. (See Shah, S., & T. Vatsal, 2010, p. 130, for a similar example attributed to early 19th century Gujarat.)

Such smock-like garments were made from a single piece of silk or satin cloth, usually embroidered with Chinese designs in white or cream silk thread. They were stitched on the side with an opening at the neck which is gathered with a ribbon or in the later pieces the area around the neck is embroidered to define the area as in the piece you have shown. They were worn over loose Chinese pyjamas which were embroidered at the hem and known as an

ijar. Typically, they were worn by Parsee children on ceremonial occasions such as before the initiation ceremony.

Embroidered garments imported from Canton became popular with the Parsees of Gujarat in the nineteenth century. Many Parsee merchants had agencies and trading houses in Hong Kong and Shanghai as they did elsewhere in Asia, so it was a relatively simple matter for the Parsee community to access Chinese embroidered items for the market back home. The popularity of these Chinese-made textiles became such that the Parsee community began to embroider their own silk garments in the Chinese style. The town of Surat in western India, which had a significant Parsee population, was also home to a long-established embroidery industry, and so Surat became the centre of Parsee embroidery in the ‘Chinese’ style (Shah & Vatsal, 2010, p. 114).

Local tastes and idiosyncracies crept in as a consequence of local production. The quirky motifs shown on the

jhabla here are typical of those used on locally-made jhablas, Parsee saris (garas) and so on.

The phoenix-like birds that one would expect to see on a Chinese textile here take on more of the appearance of a cockerel or long-tailed rooster for example. Also, pairs of feeding roosters are depicted. For the Parsees, roosters are associated with good beginnings and most probably the sun and solar symbols, given that roosters crow as the sun rises.

The Parsees, who follow the ancient religion of Zoroastrianism, first came to India from Persia in the 8th or tenth century, fleeing religious persecution. Today, probably there are about 125,000 Parsees or Zoroastrians worldwide. About 70,000 live in Mumbai/Bombay, a city of 14 million people. Another 1,700 live in Karachi in Pakistan. The Parsees of India and Pakistan are a distinct but exceptionally successful commercial minority. By the nineteenth century, Bombay’s Parsee families dominated the city’s commercial sector, particularly in spinning and dyeing and banking. Wealth from these activities was put into property so that by 1855, it was estimated that Parsee families owned about half of the island of Bombay. Today, India’s most prominent Parsee family is the Tata Family, founders and owners of India’s most prominent conglomerate the Tata Group. Despite their wealth, India’s Parsee community is hugely respected and admired in India because of the community’s humility and charitable works which extend way beyond serving members of their own community.

Well-off though they are as a community, the Parsees are dying out. It has been estimated that a thousand Parsees die each year in Mumbai, but only 300-400 are born. Today, one in five Mumbai Parsees is aged 65 or more. In 1901 the figure was one in fifty. Low birth rates are the main factor. Probably no Parsees remain in Burma today.

The vest here is in very fine condition. It is complete and without insect holes, repairs, or loose threads to the embroidery. The front has been more exposed to light and so has faded more than the back, but otherwise, it an increasingly rare and museum-quality piece.

References

Firoza Punthakey Mistree, pers. comm. April 2016.

Shah, S., & T. Vatsal,

Peonies & Pagodas: Embroidered Parsi Textiles – The Tapi Collection, Garden Silk Mills, 2010.

Stewart, S. (ed.),

The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination, SOAS, 2013.Provenance:

UK art market

Inventory no.: 3456

SOLD