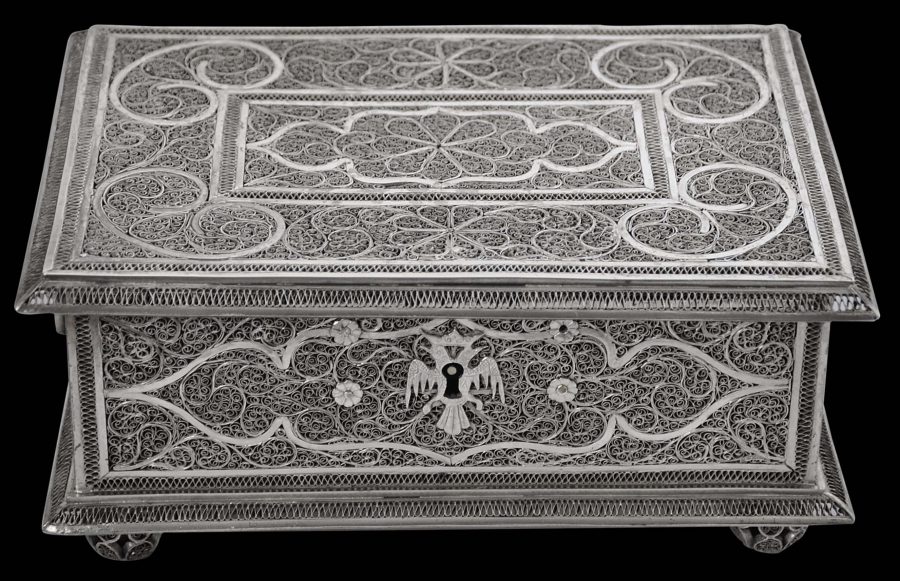

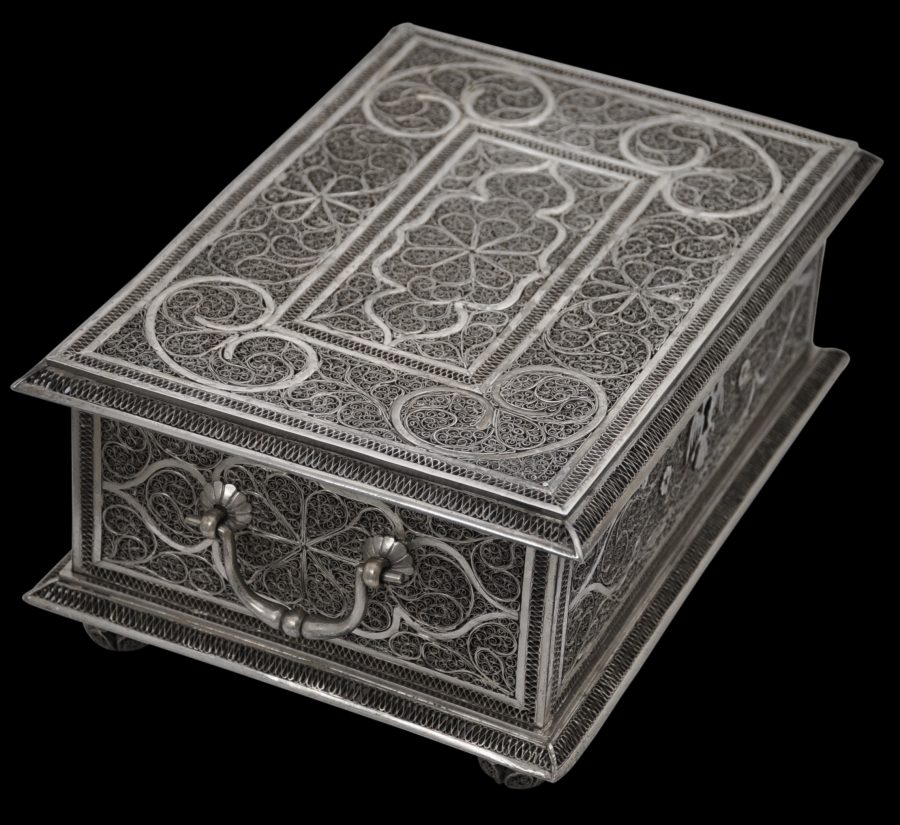

This unusually large and heavy silver filigree lidded box was originally intended to serve as a betel box, probably for use by a senior Dutch colonial official. The original silver sheet dividing compartments to allow the box to be used for betel are still inside (usually, these are no longer present, having been melted down over the intervening centuries.)

The sides and hinged cover are all of silver filigree – a combination of broader, flatter wires, and thinner, twisted wires. The base is of sheet silver, as are the internal dividing inserts.

The original silver lock is present, as are the original internal silver chains that connect the lid to the base to support the lid when it is open. The key is no longer present.

The key hole is covered with an engraved escutcheon in the form if a crowned double-headed eagle. This is a symbol associated with European royalty but also with the royal house of Mysore in India, where the symbol is known as the Gandaberunda. The Russian royal family also used the symbol, and indeed, much silver filigree produced in Asia founds its way to Russia via the trading activities of the Dutch East India Company (VOC).

There are solid cast silver handles on either side. The box sits on four elaborate spherical feet composed entirely of lappet panels of silver filigree.

The box was made either in India or the East Indies, possibly Batavia but perhaps also Sumatra. Usually such filigree items are ascribed to India, often Goa, for the European market. But another view is that such items were made in the East Indies on behalf of the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) or at least for the Dutch market. Items with similar styles of filigree that are attributed to either India or Southeast Asia are illustrated in Piotrovsky (2006. pp. 64-67). It is possible that silver filigree of this type which has been found in India was not made there but traded there by the VOC and was originally made in the Dutch East Indies.

Other related pieces are illustrated in Jordan (1996, pp. 212-214). These pieces, ascribed to seventeenth century India, feature similar filigree work, including zig-zag borders that can be seen in the piece here.

The main objective of the VOC was to bring spices from Asia to Europe. But the VOC also established a complex series of intra-Asia trade networks whereby items were purchased in one part of Asia to be sold in another for profit. One study identifies 1,059 ships in the employ of the VOC which routinely took part in trade within Asia between 1595 and 1660 (Parthesius, 2010, p. 13). Textiles were a mainstay of intra-Asia trade but other consignments included luxury goods, timber, Chinese porcelain, and even elephants. Items of silver were produced in and near Batavia at the behest of the VOC and there was a history of silver filigree production in the area. William Marsden in his treatise on Sumatra first published in 1784 includes an extensive description of gold and silver filigree work carried out in Sumatra, with the observation that: ‘there being no manufacture in that part of the world, and perhaps I might be justified in saying, in any part of the world, that has been more admired and celebrated than the fine gold and silver filigree of Sumatra. This indeed is, strictly speaking, the work of the Malayan inhabitants’. He adds that ‘The [local] Chinese also make filigree, mostly of silver, which looks elegant, but wants likewise the extraordinary delicacy of the Malayan work.’ Sumatra was an important market for Indian-made textiles imported by the VOC. Pepper and gold were among the goods that the VOC received in payment. Undoubtedly, filigree work was too, all of which would have been trans-shipped through Batavia. It is a possibility that has been explored by Veenendaal (2014) who illustrates a series of chests with similar filigree which he attributes to West Sumatra, circa 1700.

The box here is in excellent condition with no obvious losses to the filigree and no dents or splits. Minor mis-shaping here and there can be accounted for by use and age. The box is heavier and larger than other examples we have seen. It is a museum-quality piece.

References

Jordan, A. et al, The Heritage of Rauluchantim, Museu de Sao Roque, 1996.

Marsden, P., The Wreck of the Amsterdam, Hutchinson, 2nd ed., 1985.

Marsden, W., The History of Sumatra: Containing an Account of the Government, Laws, Customs and Manners of the Native Inhabitants, with a Description of the Natural Productions, and a Relation of the Political State of that Island, 1784.

Parthesius, R., Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters: The Development of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) Shipping Network in Asia 1595-1660, Amsterdam University Press, 2010.

Piotrovsky, M. et al, Silver: Wonders from the East – Filigree of the Tsars, Lund Humphries/Hermitage Amsterdam, 2006.

Veenendaal, J.,Asian Art and the Dutch Taste, Waanders Uitgevers Zwolle, 2014.