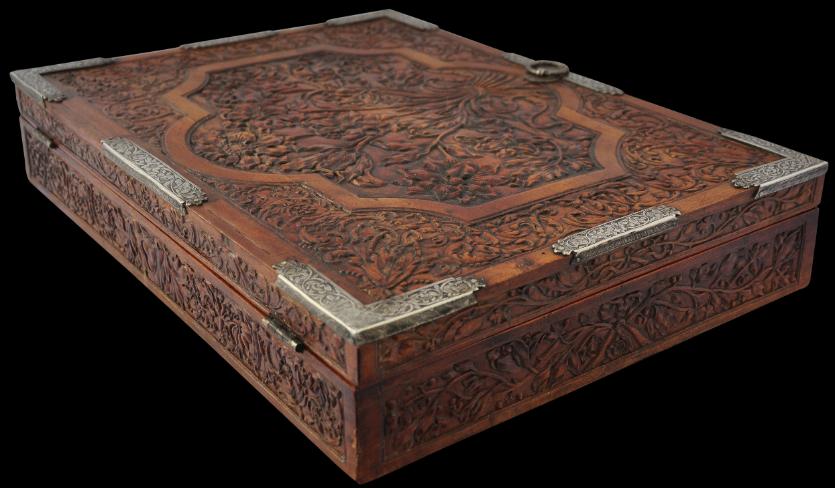

Colonial Sri Lankan or Indian Writing Box

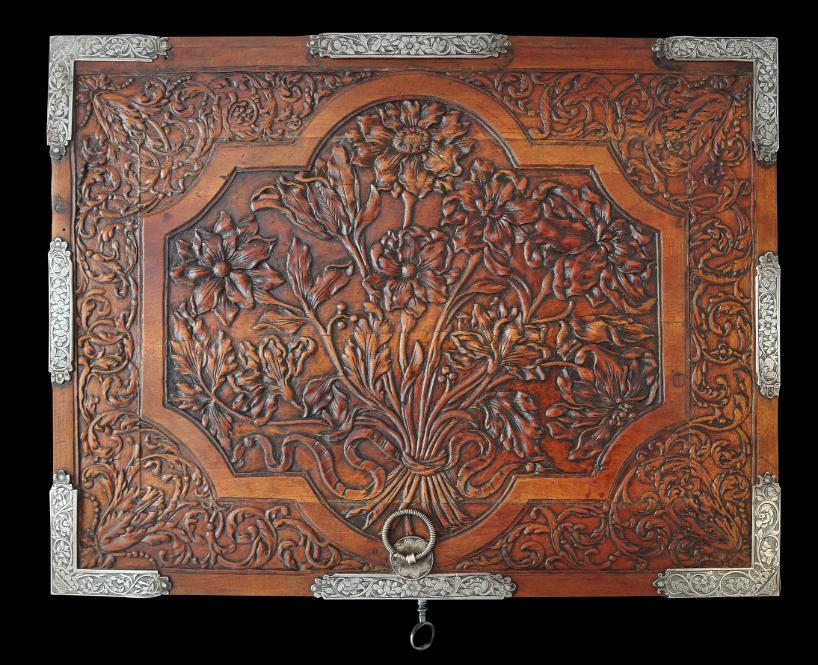

Carved Wooden Writing Box with Engraved Silver Mounts

Probably Coromandel Coast, India

18th century

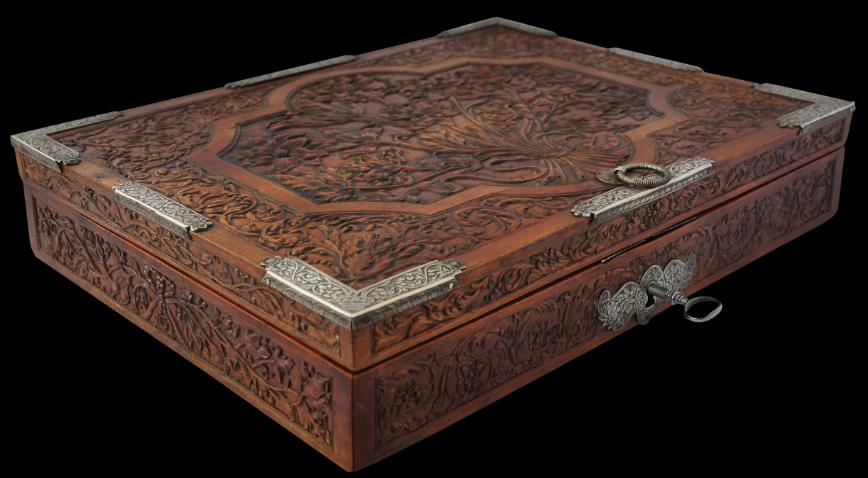

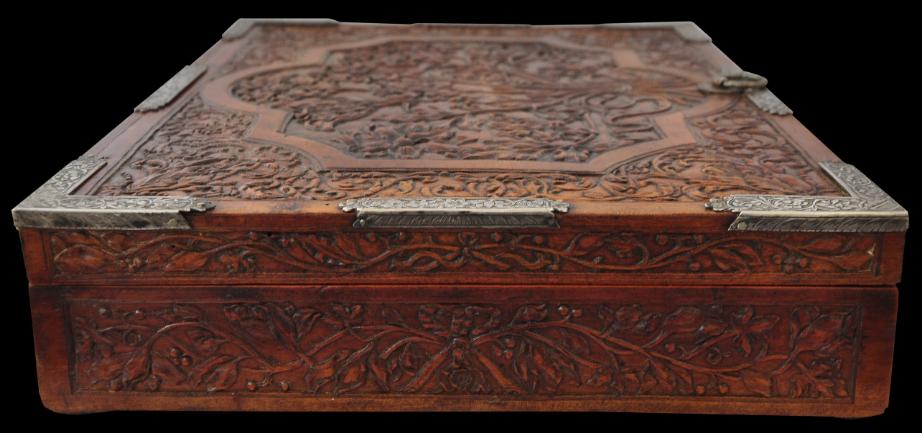

length: 33cm, width: 25cm, height: 6cm

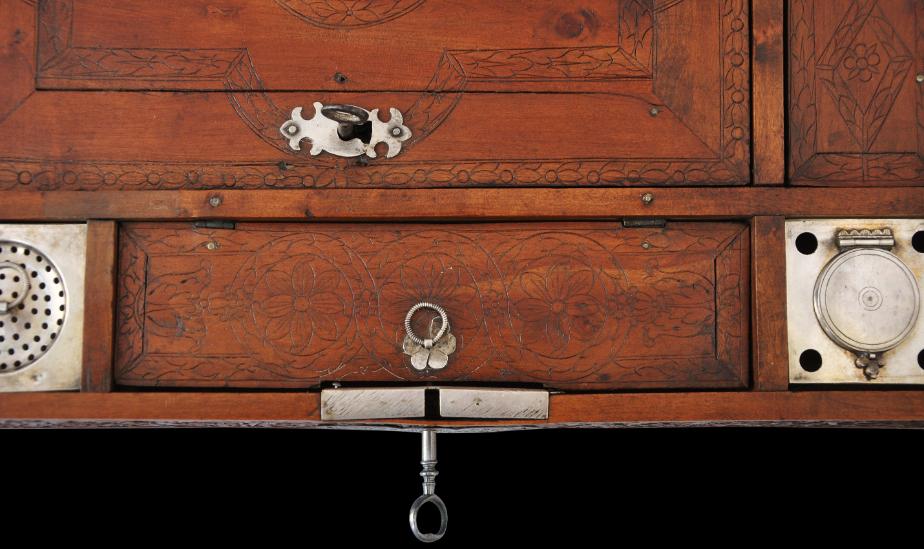

This extraordinary writing box is in exceptional for both the fineness of the carving work and its excellent condition. It comprises a shallow box on four small feet, a hinged cover, an internal writing slope and doored compartments for writing instruments, a silver ink well with a hinged cover and a silver sand sprinkling box. The overall writing box has silver mounts finely engraved with scrolling flower and foliage motifs.

The edges of the box are carved with foliage and berries. The cover is decorated with an exquisitely carved spray of flowers and leaves in the style of a seventeenth century European botanical drawing. The wood used appears to be Ceylon Satinwood (

Chloroxylon Swietenia) with a reddish stain. The grain is relatively dense and ribbon-like ‘bee’s wings’ markings are evident here and there, which is characteristic of this wood. Ceylon Satinwood grows in Sri Lanka and India.

The internal fittings are decorated with roundels filled with petals and other typically Sri Lankan or Indian lotus motifs. Such patterns are found engraved on the bases of Sri Lankan and South Indian silver

paan or betel boxes for example. Examples of this motif is illustrated in Coomaraswamy (1956, p. 96). There are similarities between some of the carving work on the exterior of this box and that offered by Christie’s London in its ‘Art of the Islamic and Indian World’, April 4, 2006, as Lot 195, described as ‘a carved padouk chest, Sri Lanka, late 17th or 18th century’.

The carving work on the top and sides panels has plenty of analogies from India and Sri Lanka. Flowers carved branching out in naturalistic patterns often are encountered on

dado panels (the panels on the lower walls of shrines and similar that are set off by decoration, often floral) in northern India such as at the Taj Mahal and Jaipur’s Amber Fort (see below for an example). They are also seen on northern Indian red sandstone architectural panels that also date to this period.

These panels were based on sixteenth and seventeenth century Dutch scientific herbariums which Mughal Emperor Jahangir’s painters had consulted for their court miniatures, (Koch, 2006). Characteristic of these floral representations is their symmetry and botanical detail. However, the detail often is not accurate and it is often not possible to accurately identify any particular species from their rendering by Indian artisans. A departure with this box is that the main floral design on the lid of this box is balanced rather than symmetrical. (The herbariums comprised actual pressed botanical specimens so although pressed, would have retained some form in relief much like the work on this box.)

A seventeenth-eighteenth century wooden cabinet with carved ivory panels in London’s Victoria & Albert Museum (illustrated in de Silva, 1975, p. 301) has fine scrolling work with berries that has some parallels with the work on the sides of this box. An ivory box also in the V&A, attributed to circa 1700 Sri Lanka, and also illustrated in de Silva (1975, p. 307) has bold carved flower-work that bears some resemblance to the top panel of this box.

A chest with ivory panels profusely carved with scrolling flowers and attributed to either Batavia or the Coromandel Coast (1680-1720) which is in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum is illustrated in Veenendaal (1985, p. 66). The relief work on this chest has some parallels with the relief work here. There are some parallels too with Sri Lankan relief work and as Veenendaal comments (page 65), “The narrow strait between Jaffna and India was no great barrier for the many ships which plied an intensive trade along these coasts. The frequent immigration of Tamils also meant that the cultural influence of the sub-continent had always been extensive. The result is that any eventual differences in furniture styles (on cabinets or boxes) between the Coast and coastal Sri Lanka must have been minimal.”

Many boxes of wood and tortoiseshell from India and Sri Lanka and of the period have silver mounts engraved with similar foliage and floral scrolling. Jackson & Jaffer (2004, p. 36) illustrated a tortoiseshell casket from sixteenth or seventeenth century India with silver mounts that are similarly engraved. Other examples are illustrated in Tchakaloff

et al (1987, p.98), and still more in Jordan et al (1996).

The sides of all the silver mounts are engraved with bands of lotus petals in a manner not unlike that used for the outer border of a silver plate illustrated in Voskuil-Groenewegen (1998, p. 88) which is attributed to mid-eighteenth century Sri Lanka.

Senior officials of and merchants in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) were required to routinely send written communications about trade, local political developments, culture and any other events or observations deemed potentially useful for the Company’s interests. And usually everything had to be copied three or four times. (Veenendaal, 1985, p. 85). Accordingly, portable writing cabinets and boxes were much in demand in eighteenth century Batavia, India and Sri Lanka. This example appears to be one such box. Its precise origins are not clear. India’s Coromandel Coast seems most likely but Goa, Sri Lanka and Batavia are possibilities too. In any event, this writing box is one of the finest examples we have encountered.

References

Coomaraswamy, A.K., Mediaeval Sinhalese Art, Pantheon Books, 1956; de Silva, P.H.D.H., A Catalogue of Antiquities and Other Cultural Objects from Sri Lanka (Ceylon) Abroad, National Museums of Sri Lanka, 1975; Veenendaal, J., Furniture from Indonesia, Sri Lanka and India During the Dutch Period, Foundation Volkenkundig Museum Nusantara, 1985; Jordan, A et al, The Heritage of Rauluchantim, Museu de Sao Roque, 1996; Tchakaloff, T.N. et al, La Route des Indes – Les Indes et L’Europe: Echanges Artistiques et Heritage Commun 1650-1850, Somagy Editions d’Art, 1998; Potter, T., Wood: Identification and Use, Guild of Master Craftsman Publications, 2004; Voskuil-Groenewegen, S.M. et al, Zilver uit de tijd van de Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, Waanders Uitgevers, 1998; Jaffer, A., Luxury Goods from India: The Art of the Indian Cabinet Maker, V&A Publications, 2002; Jackson, A. & A. Jaffer, Encounters: The Meeting of Asia and Europe 1500-1800, V&A Publications, 2004; Koch, E., The Complete Taj Mahal, Thames & Hudson, 2006.

Inventory no.: 1012

SOLD

A late 16th century marble panel (and detail) from the Amber Fort in Jaipur, Rajasthan. Work such as this appears to be the inspiration for this box. (Image taken in 2009.)

Click on the video to get a better idea of the relative size of this item.