This large, silver-mounted ewer comprises half a double Seychelles or coco-de-mer nut (Lodoicea maldivica) as the body for the vessel. It is from the Indian colonial Portuguese enclave of Goa, and would have been used in a Catholic church or monastery in the city, initially as a pouring vessel, and then later as storage box, most probably for incense. The nut itself is from a palm that grows on only two islands in the Seychelles in the Indian Ocean.

The vessel stands on a tall, splayed silver foot, with a baluster column leading to the nut. Hinged and pierced silver brackets hold the nut in place. The top of the nut is closed over with a silver covering in which sits a hinged lid. The head of an Indian pea hen takes the place of the spout.

The silver is repoussed with rococo-like decorative elements. The silver panel atop the nut is repoussed in relief with an eagle, shell-like scrolls, and a wonderful highly stylised tulip-like floral spray that is often seen on Iberian and Dutch silver of the 16th-18th centuries. This type of decoration can be seen in colonial silver from South America, to Sri Lanka, the Dutch East Indies and of course Indo-Portuguese Goa. Penalva (2014, p, 157) illustrates a gold and copper hair ornament attributed to 19th century Goa which is decorated with very similar motifs. The eagle motif (and more specifically, the double-headed eagle) was adopted by the royal house of Mysore (near to Goa) as an emblem. Bennett & Kelty (2014, p. 128) illustrate a silver reliquary coffer attributed to late 17th century Goa which includes related decoration, and also a silver incense boat attributed to 17th century Goa (p. 136). Curvelo (2008, p. 64) illustrates an altar cross from Goa inscribed ‘1743’ and which has very similar silverwork to that seen on our vessel.

The use of coco-de-mer shells for vessels has parallels with European sixteenth century usage. A handful of coco-de-mer nuts with silver-gilt mounts are known in several European museum collections. The nuts are of Seychelles or Maldives origin and the mounts are either Portuguese, German, or Goan. According to MNAA (2009, p. 85), a letter written in 1579 from Goa by the Provincial of the Company of Jesuits, Rodrigo Vicente, to the Jesuit Superior General Everard Mercuriano, mentions that even in Goa, Seychelles nuts were being set in silver.

The form here – the wide foot, the high stem, the hinged-bracket mounts – is a direct copy of those that were made in Europe, probably initially in the Hapsburg-controlled areas. These included much of the Iberian peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and so the form spread to Spain and Portugal. The use of the eagle as an emblem of the state and the Hapsburg dynasty also spread to Spain and Portugal. From here, the form seems to have spread to Goa. The form is reminiscent of a boat and that might be intentional – the nuts were believed to have come from the sea and their arrival in Europe was very much the product of trade. Various museums in Europe have example, including the British Museum.

The use of hinged mounts to encase the nut is another interesting affectation. This is in keeping with other precious materials being encased in silver and gilded silver from the 16th century onwards. When items were deemed to be precious on account of their curative nature especially, none of the material was wanted to be lost or damaged. This meant that drilling the nut to secure the mounts was out of the question. Using hinged casing allowed the nut to be mounted in an unobtrusive manner, but also permits the mounts some give should the nut expand.

Emperor Rudolf II (b. 1552-1612), a member of the Hapsburg Dynasty, and who was also Holy Roman Emperor (1576–1612), King of Hungary and Croatia (as Rudolf I, 1572–1608), King of Bohemia (1575–1608/1611) and Archduke of Austria (1576–1608) is recorded as having 18 coco-de-mer nuts in his Kunstkammer or cabinet of curiosities, for example (Stark, 2003-04).

The belief in Europe at the time was that such nuts originated from the sea, hence their name – literally, ‘coconut-of-the-sea’. The nuts were thought to have curative properties for illnesses such as colic, paralysis and gout, and to counteract the effects of poison, with these benefits being passed to water stored in vessels made from the nuts. The nuts came to be seen as more powerful in treating poison than even bezoar stones. In 552, the Portuguese humanist and writer Joao de Barros wrote that ‘experience shows that the inner husk of [the nut] is much more efficacious against poison than the bezoar stone’ (Stark, 2003-04).

A Portuguese doctor based in Goa published an account in 1563 in which he commented that the nuts come in pairs and that no-one had ever seen a nut growing on a tree but that their source was the ocean. The nuts were comparatively scarce and were highly prized.

Interestingly, Goa became the main source of these nuts for the European market. They were not indigenous to Goa or anywhere near it; but Goa became the world’s most important clearing centre for exotic goods by the 16th century and so were brought to Goa for sale to European merchants.

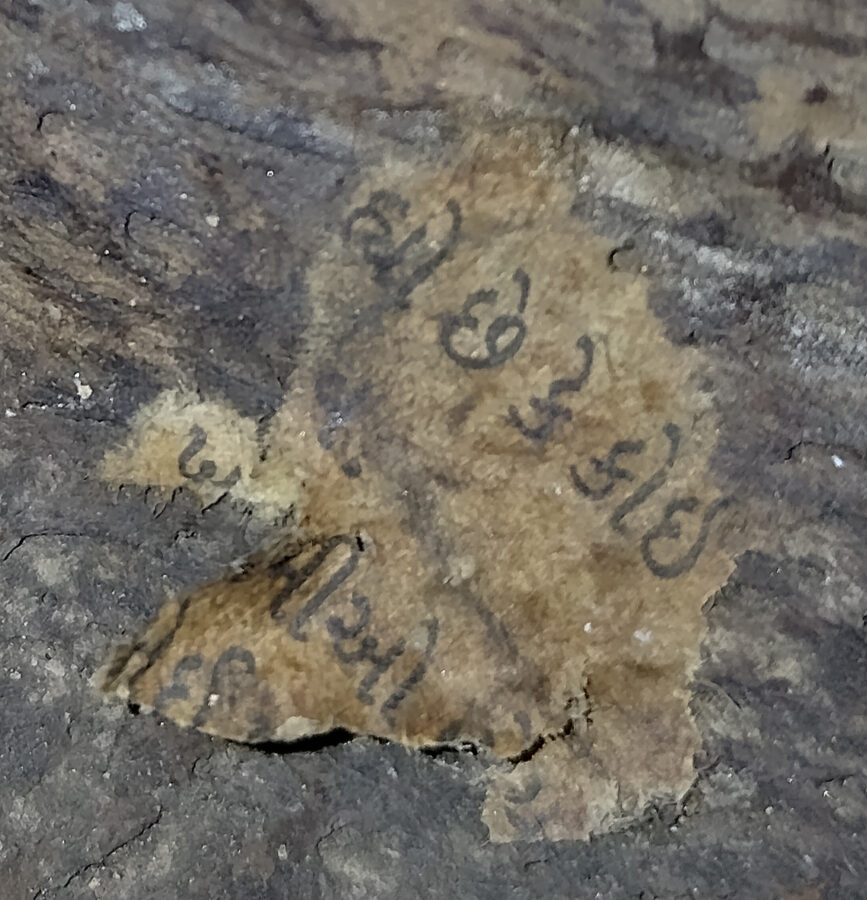

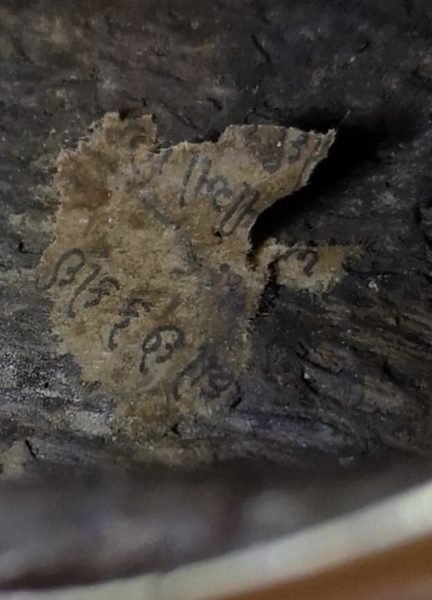

The vessel was acquired in the UK but its origins in India have been confirmed. Careful inspection of the interior of the example here yielded this small fragment of early paper attached to the side of the nut. It is inscribed with several characters of what Dr Christopher Miller (a Canada-based independent specialist in Indic scripts) has kindly identified as Gujurati script. The script is likely to be printed (rather than handwritten) and there is an insufficient amount of script for a meaningful translation, but it is unlikely that the text has anything to do with the vessel itself. It seems likely that a piece of paper was used at some stage to wipe the vessel out and this (now old) fragment was left behind. The main benefit of this is to confirm the vessel’s origins and mounts as being in India.

The ewer is in fine condition. There are no dents, losses or breaks. There is a small, stable and very old crack to the nut towards the back but there is no movement and the crack itself has age and patina. Overall, the ewer is tall, sculptural and has a tremendous decorative presence matched by its rarity.

References

Bennett, J., & R. Kelty, Treasure Ships: Art in the Age of Spices, Art Gallery of South Australia, 2014.

Curvelo, A., et al, The Orient Museum, Lisbon, Reunion des Musees Nationaux, 2008.

Haag, S., & F. Kirchweger (eds.), Treasures of the Hapsburgs, Thames & Hudson, 2012.

Jordan-Gschwend, A, & K.J.P. Lowe (eds.), The Global City: On the Streets of Renaissance Lisbon, Paul Holberton Publishing, 2015.

Milller, Christopher, Canada, Pers. comm.

Moore, A., N. Fils, & F. Vanke (eds.), The Paston Treasure: Microcosm of the Known World, Yale University Press, 2018.

Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga (MNAA), Portugal and the World: In the 16th and 17th Centuries, Lisbon, 2009.

Penalva, L. et al, Espendores do Oriente: Joias de Ouro da Antia Goa/Splendours of the Orient: Gold Jewels from Old Goa, Museu Nacional de Atre Antiga, 2014.

Stark, M.P., ‘Mounted bezoar stones, Seychelles nuts, and rhinoceros horns: Decorative objects as antidotes in early modern Europe’, Studies in the Decorative Arts, Fall-Winter 2003-2004.

Thornton, D., A Rothschild Renaissance: Treasures from the Waddesdon Bequest, The British Museum, 2015.