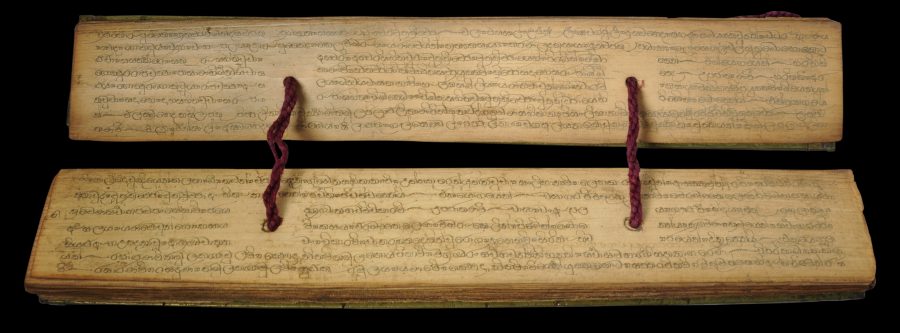

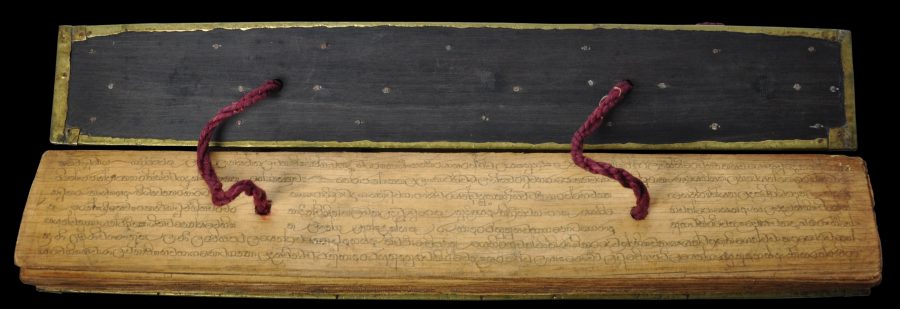

This well-preserved fine and relatively early Sinhalese ola manuscript comprises 30 leaves and a pair of covers. Each page is of trimmed palm leaf with seven fine lines of particularly flowery Sinhalese script on both sides. There are no images, as is usually the case with Sinhalese palm leaf manuscripts.

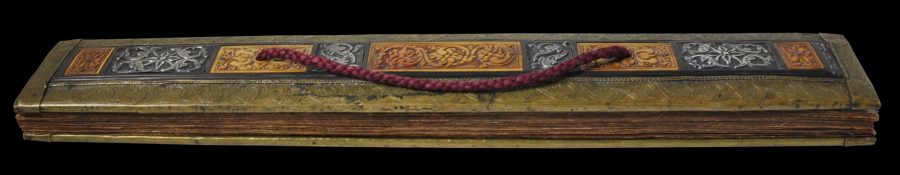

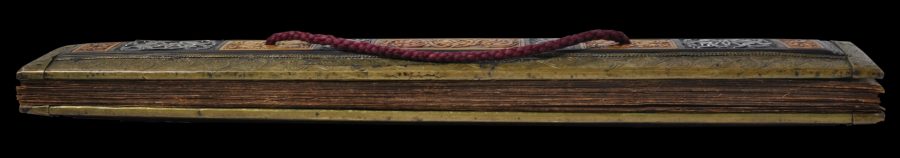

The outwards-facing surfaces of the covers, which have bevelled outer edges and are of black ebony wood, are clad in thin, sheet brass. The edges are engraved or incised with typically Kandyan scrolls. It is likely that the brass originally was silvered. The raised mid-section is inset with alternating carved tusk and repoussed silver plaques. This is the case with both covers, which are finished in an identical manner. Such decoration is unusual. Typically, ola wood covers are simply painted.

The low-relief but beautifully rendered flowing scrollwork of the floral panels is akin to that seen on boxes and coffers made for the Portuguese market in the 16th and 17th centuries (see Jordan-Gschwend & Beltz, 2010 for examples).

A red, cotton cord holds the manuscript together.

Such manuscripts were typically prepared for libraries attached to Sri Lankan Buddhist monasteries. Many of these are now held in the Colombo Museum Library in Sri Lanka which now holds around 5,000 palm leaf manuscripts.

Most Sri Lankan palm leaf manuscripts are written on the prepared leaves of the Talipot palm (Corypha umbraculifera). It is one of the largest palms to grow in Sri Lanka and grows to a height of 15-35 metres. The trees take 40 to 100 years to reach maturity and before the tree dies, it shoots out from its top an inflorescence that can be as long as 7 metres.

The material used for preparing the writing leaf is taken from young trees and from the unopened leaf buds of such trees. Each leaf bud grows to 3 to 7 metres long and can hold up to 100 leaflets.

The preparation of the writing leaf required much care. A young tree would be selected and when the leaf bud was about to burst open it was cut off and slit open. The leaflets were then separated and removed one by one. The midribs of the leaflets were removed and the leaflets were them immersed in a vessel filled with cold water.

The vessel was then placed over a slow fire until the water reached boiling point. Thereafter the heat was reduced and the leaflets were allowed to simmer for several hours. The leaflets then were taken out and allowed to dry for three days in the sun. Thereafter the leaflets were exposed to the cooler night air for three nights, allowing them to become supple.

The next stage of the preparation process involved each leaf blade being weighted and then pulled up and down over the smooth surface of a cylinder of wood which was usually the smoothed trunk of an areca palm (the tall, thin palm that produces betel nut.)

The manuscript pages then were cut from the leaves. They were punched with one or two holes using a steel punch. The holes later were used in the filing of the pages – a bamboo slither was passed through a hole in each page so that all the pages could be held together. Held together, the edges of the pages were then singed with a hot iron and burnt to remove any irregularities so that each page would be of uniform length and width.

Writing on each page was done with a style that had a steel point which was sharpened from time to time on an oiled stone. The writing then had to be blackened otherwise it was too faint. This was done with ink made from combining fine dust made from charcoal from leaves, commonly cotton plant leaves, with an alluvial resin. The mixture was heated until a black resinous oil was produced. This was rubbed over the manuscript pages with a cloth so that the whole page was covered with black. This was then rubbed away with sifted rice bran, leaving the black resin in the scratched depressions left on the page by the style.

As mentioned, palm leaf books were not normally illustrated.

Once the pages were finished, two covers were produced for them. These were made to size. The edges almost always were bevelled and the inner and outer surfaces usually were painted, usually with colourful designs. The covers were made from one of various types of local woods such as ebony (as is the case here), iron wood, val sapu, gammalu, jak or milla.

The leaves of the book and the covers then were strung together with a cord, either a cotton cord or one made from the fibre of the niyanda leaf.

The example here is in fine condition. There are no significant losses. Each element has wonderful patina indicating its significant age. The ola was acquired in the UK and almost certainly has been in the UK since colonial times.

The last few images show:

Talipot palms, Kandy, central Sri Lanka. Photographed February, 2011.

The monastery of Potgul Magila Vihara, central Sri Lanka, which holds perhaps central Sri Lanka’s most extensive collection of ola manuscripts (Photographed February, 2011).

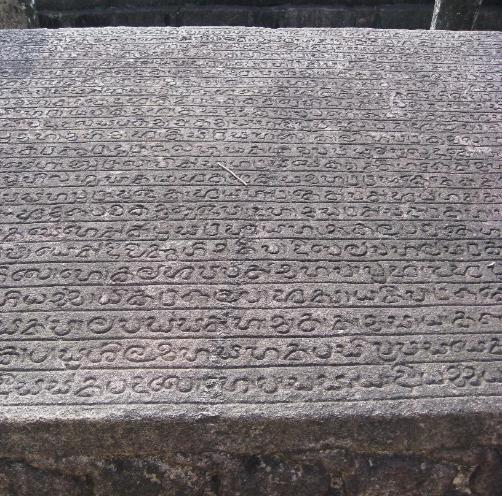

The giant inscribed tablet at Polonnaruva in central Sri Lanka, in the shape of a large palm leaf manuscript. It was completed during the reign of King Nissankamalla (1187-1196AD). (Photographed February, 2011.)

High priests reading from palm leaf books, circa 1900.

References

Jordan-Gschwend, A., & J. Beltz, Elfenbeine aus Ceylon: Luxusguter fur Katharina von Habsburg (1507-1578), Museum Rietberg, 2010.

De Silva, W.A, Catalogue of Palm Leaf Manuscripts in the Library of the Colombo Museum, Volume 1, 1938.