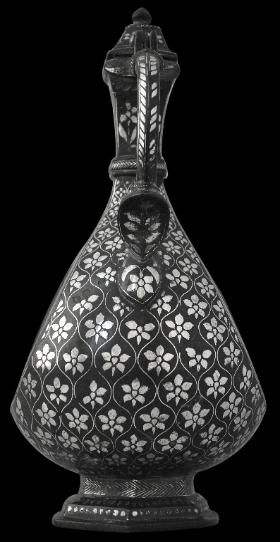

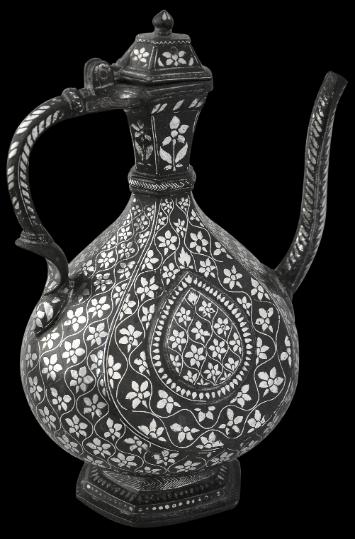

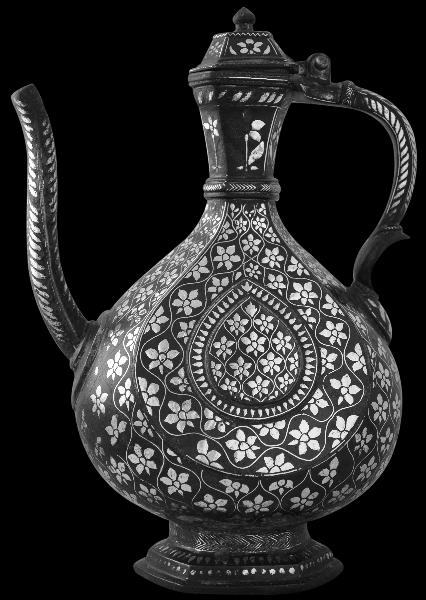

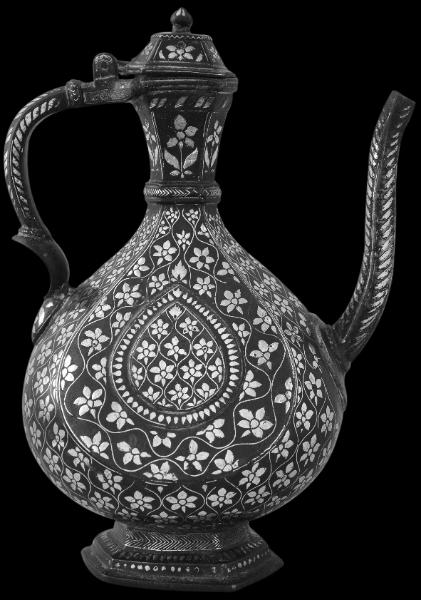

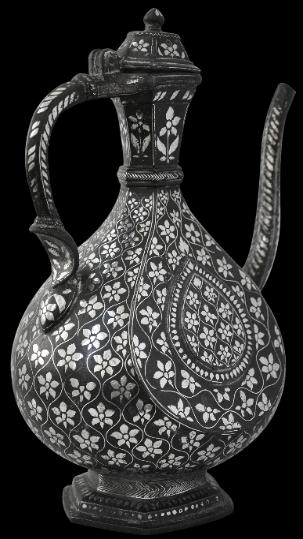

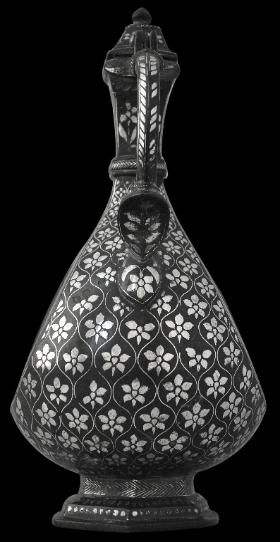

Bidri Ewer, India

Bidri Ewer (Aftaba)

India

18th century

height: 29cm, weight: 1,830g

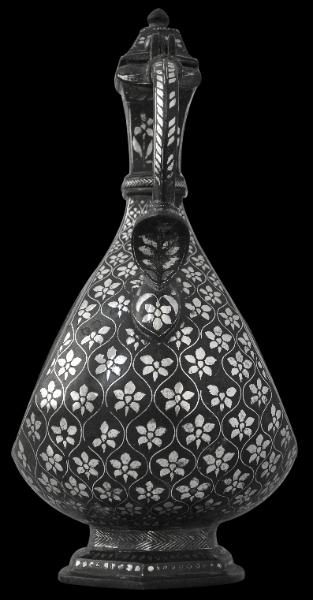

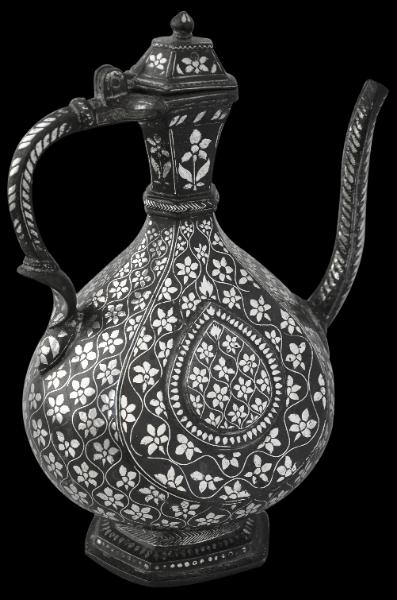

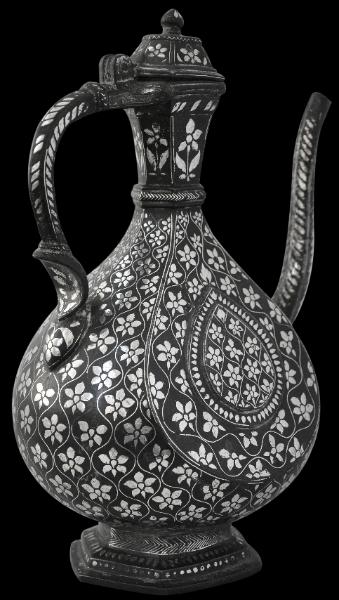

This north Indian ewer is covered with silver-inlaid Bidri work. It has a wonderful tear-drop body with tapering sides. It stands on a tiered, flared foot of six sides. The handle is curved and the spout has a gentle ‘S’ shape. The spout seems to end abruptly – but this was the style of some Bidri ewers – see Lal (1990, p. 80) for a similar example in New Delhi’s National Museum. The ewer retains its original lid which has a tapering, rectangular form with a bud-like finial.

The silver inlay decoration completely covers the ewer. Mostly, it is of trellis form with an open flower motif in each field. The spout, handle and part of the foots are decorated with chevron or tiger-stripe patterns.

The chevron/tiger-stripe patterns convey a sense of flowing water, both in terms of the ‘streams’ which one would expect to find in a Mughal garden, and, by dint of both the direction of travel – a sense of movement is achieved that would be lacking in a strictly repeated floral design (Thomas, 2011.)

Typical Islamic ewers comprised a central chamber to which a spout, foot, handle and neck were attached. They permitted water to flow – Koranic injunctions deemed flowing water to be ‘clean’. Ewers were introduced to India by Muslim invaders during the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. Thereafter their designs were Indianised – the ewers became more curvaceous and were decorated with lush plant and floral motifs.

In India, local Muslims used such vessels for handwashing. They became a practical tool of hospitality, being used to welcome visitors by pouring scented water over the hands and feet and into a basin. In this way, the motifs employed on such vessels in Northern India can be seen as particularly appropriate: the scrolling arabesques and trellised cartouches of floral sprays can be seen as representative of a paradisical garden, a destination of pleasure and balm – the orderly, repeated pattern of floral cartouches can be seen as representing the ordered layout of the idealised Islamic garden (Thomas, 2011).

Bidriware originated in the city of Bidar in the Deccan. It is cast from an alloy of mostly zinc with copper, tin and lead. The vessels are overlaid or inlaid with silver (as is the case here), brass and sometimes gold. A paste that contains sal ammoniac is applied which turns the ally dark black but leaving the silver, brass and gold unaffected.

Bidriware caused great interest at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851. It found new European markets and helped to keep alive the craft as demand fell in India with the decline of many of the smaller courts and landed families.

The ewer here though is of a style more in keeping with the eighteenth century. There are some losses to the silver inlay as is common with earlier Bidriware. There are no cracks, dents or repairs. Overall, it is a sculptural and fine example of an increasingly rare Bidri form.

See Lot 242, Christie’s London, ‘Arts of the Islamic and Indian Worlds: Including Works from the Simon Digby Collection’, April 7, 2011, for a Bidri ewer of similar form (but ascribed to the seventeenth century.)

References

Lal, K.,

Bidri Ware: National Museum Collection, National Museum New Delhi, 1990.

Stronge, S.,

Bidri Ware: Inlaid Metalwork from India, Victoria & Albert Museum, 1985.

Thomas, D.,’The carnation ewer – an example of Ottoman influence on North Indian ewers’, unpublished paper, 2011.

Zebrowski, M.,

Gold, Silver & Bronze from Mughal India, Alexandria Press, 1997.

Inventory no.: 1543

SOLD