Enquiry about object: 9944

Burmese Glazed Earthenware Wall Tile

Burma (Myanmar) late 18th century

height: 17.7cm, width: 17.9cm, depth: 5cm, weight: 2,332g

Provenance

Scottish art market

This particularly well-preserved tile, of brown earthenware, is coated with a thick monochromatic olive-green glaze. It has been moulded to show a figure astride what is probably a sacred goose or hamsa, within a wide, impressed border.

The lower section of the tile has remnants of gold leaf suggesting that in its later life it was used for religious purposes – dabbing items with gold leaf in this manner was usually meant as a merit-earning offering in Burma.

It is likely that the tile is from Mingun, near Mandalay in Upper Burma.

There are other tiles that seem related though usually they are are larger. These were commissioned in the late eighteenth century by the local king for a massive temple complex near Mingun which was never completed. Because the complex was not completed, the tiles were made but not installed. Consequently several such tiles are known outside Burma, including one in the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) in London.

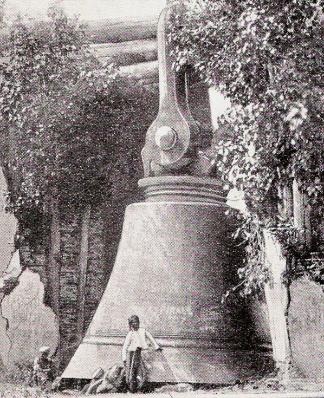

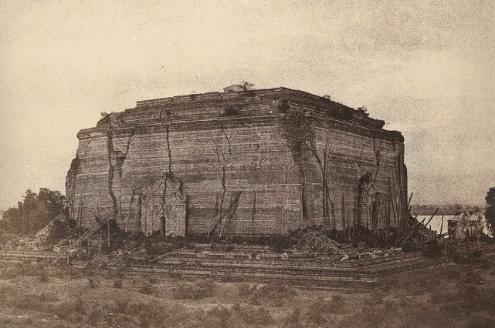

The Mingun pagoda was to be the centrepiece of an ambitious building project initiated by King Bo-daw-hpaya who ruled 1782-1819. The complex appears not to have been competed perhaps because of a shortage of funds, and then in 1839, part of the structure was damaged by an earthquake. Even in its current dilapidated state it is the largest brick temple in Asia, and possibly the largest brick pile in the world – its outline dominates the western bank of the Irrawaddy River adjacent to Mingun village. Part of the complex includes Asia’s largest solid-cast bell – 4 metres tall and weighing 90 tonnes. The bell today stands nearby the pagoda.

Fraser-Lu (1994) argues that this and the other tiles like it appear to have been the last set of religious ceramic tiles commissioned in Burma and that the tiles commissioned by King Bo-daw-hpaya probably were made by descendants of the potters that were taken as prisoners of war by Bo-daw-hpaya’s father king Alaung-hpaya after his conquest of the kingdom of Pegu in 1757. The potters were required to establish a new potting village where they accepted royal commissions after their arrival at Shewi-bo, Alaung-hpaya’s capital.

Stadtner (2011, p. 255-256) says that King Bo-daw-hpaya envisioned having his pagoda embellished with a series of glazed tiles modelled directly on those at the Ananda Temple in Pagan, which was constructed 700 years earlier. The king sent artists to Pagan to prepare drawings of over 1,500 tiles that were placed in niches in the exteri0r of the Ananda. The illustrations were reviewed by the king’s chief religious adviser in early 1791, who made some adjustments according to his reading of the Pali text, and several new themes were introduced. The tiles were then made. Each was glazed in one of three colours: white (hpyu), brown (nyo), and green (sein) which is the colour of the example here. The example here is not based on any particular tile at Ananda and so seems to be one of a series required by the king’s adviser.

The tiles were intended to be set into two slightly receding superimposed roof terraces. Stadtner (2011, p. 256) estimates that the number of tiles prepared probably would have been between 1,500 and 2,000. They were not installed but where at Mingun they were stored is not recorded. However, by the late 19th century and early 20th century a small number of tiles had entered into the Indian Museum, Calcutta, the British Museum, the Victoria & Albert Museum, and the Museum fur Indische Kunst in Berlin. Stadtner says that these and others in public collections amount to no more than thirty tiles. Other tiles were displayed on-site at Mingnun from around 1960. They were cemented to the interior walls of a brick storeroom but most were stolen in the early 1980s and are detectable by having faint traces of modern cement on their reverses (there are no such traces on the reverse of the example here.)

The condition of the example here is very good. There are no cracks or repairs. There is some surface scratching to the glaze, as might be expected.

Above left: an engraving of the giant bell at Mingun, which like the tiles, was never installed; above right: an early engraving of the Mingun Pagoda.

References

Fraser-Lu, S., Burmese Crafts: Past and Present, Oxford University Press, 1994.

Lowry, J., Burmese Art, Victoria and Albert Museum, 1974.

Stadtner, D., Sacred Sites of Burma: Myth and Folklore in an Evolving Spiritual Realm, River Books, 2011.