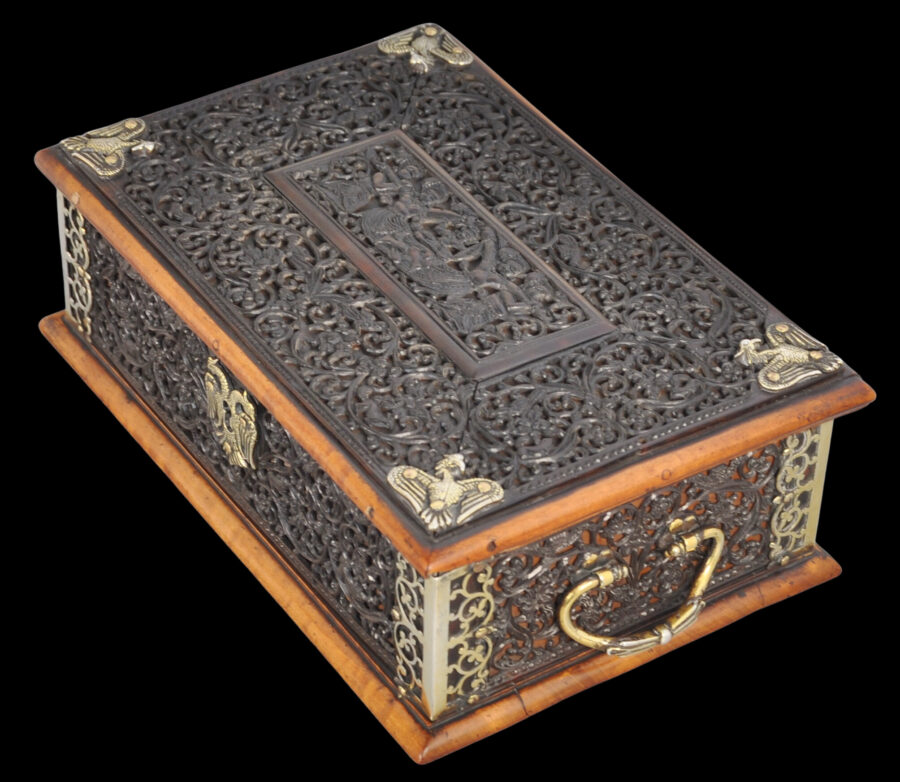

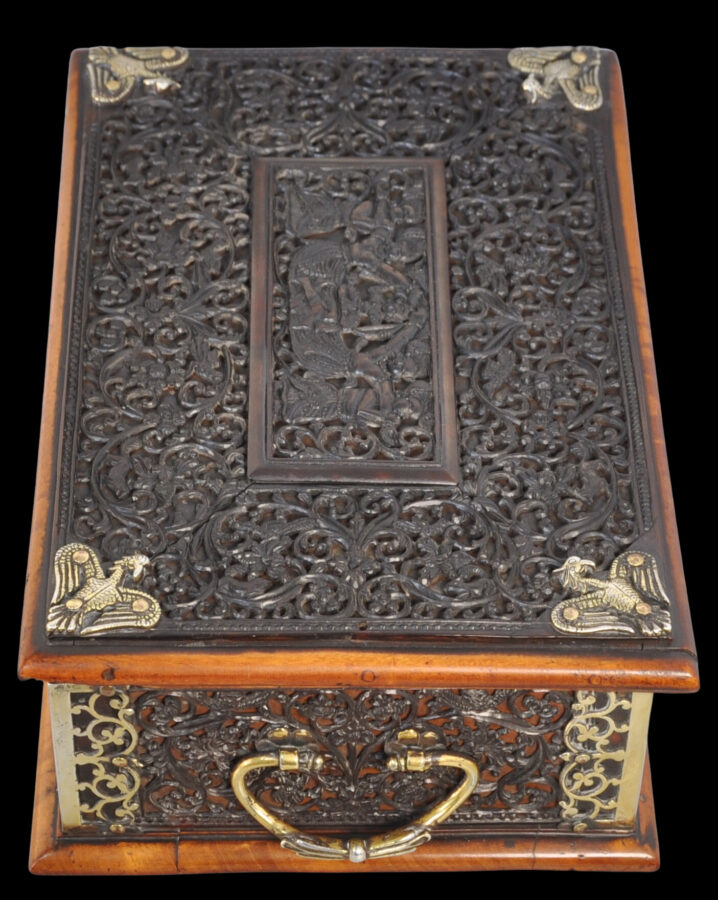

The form of this extremely rare box is European but the decoration is completely Singhalese. The excellence of the artistry and the motifs used are a direct parallel to similar boxes also produced in Sri Lanka but in ivory that date to the second half of the 17th century. The ivory equivalents are well known and are in important museum collections, including the Rijksmuseum in The Netherlands. The box here however is unique, being the only tortoiseshell example based on these ivory prototypes. As such, we regard it as an important, world-class, museum-worthy artefact which sheds new light on early Ceylonese production of luxury goods for the European market.

The box is covered on all sides and on the hinged cover with tortoiseshell panels that are pierced and carved in relief with twisting, curling mythological narilata vines which terminate in finely rendered flowers that are based on flower motifs seen on 17th century Dutch silverwork. Narilata is a mythological vine which grows on the sides of mountains and which blooms only once every twenty years. The blooms are voluptuous, luscious and are said to represent women in order to lead ascetics and hermits into temptation (Veenendaal, 2014, p. 38).

Many small squirrels and birds hide among the narilata tendrils. Below is a watercolour and pencil depiction of a Ceylonese squirrel, dated 1785, by the Dutch artist Jan Brandes, now in the Rijksmuseum. These squirrels are depicted on the box here.

The tight, pierced, foliate scrolling interspersed with small animals has parallels with pierced silverwork executed in Indo-Portuguese Goa also in the second half of the 17th century. A silver reliquary box illustrated in Chong (2016, p. 66) is one example. It comprises pierced, silver panels over a wood frame.

The tortoiseshell panels on the lid include a raised central panel that shows five entwined female figures. Formulations of this motif are known as the panca-nari-geta (5-women-knot), an ancient Sri Lankan motif. There is a fine example of this motif carved in stone at the entrance of the Sri Dalada Maligawa (the Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic) in Kandy (Coomaraswamy, 1908, p. 91). Also, an example very similar to the one here appears on a rare Ceylonese-Sri Lankan ivory box dated to the first quarter of the 17th century in the Tavora Sequeira Pinto Collection, illustrated in Vassallo e Silva (2022, p. 217).

The tortoiseshell plaques are attached to the wooden substrate by means of small tortoiseshell pegs.

The complexity of the box is enhanced by gilded silver mounts. These comprise two side handles, pierced corner supports shaped as scrolling vines, a double-headed parrot key plate and the original gilded silver key, a parrot in each corner of the lid, hinge struts with pierced finials to the back of the box, pierced hinge struts inside, and a silver plate over the top of the lock mechanism inside. The key and lock still work.

The double-headed parrot or eagle motif is known as the bherunda pakshaya in Sri Lanka. It is similar to the motifs associated traditionally with Russian and Hapsburg royalty, but might have nothing to do with these and might have evolved concurrently.

The gilded silver handles to the sides are of ‘C’ form and are attached to floral handle plates. These plates are similar to those shown on boxes or cabinets that date to ‘circa 1700’ and ‘1650-1680’ respectively in Veenendaal (2014, p. 47). The actual form of the handles though is unusual being shaped as tied ribbons which flare off the sides of the casket. They appear to relate to handles applied to the tops of some 16th century Kotte ivory caskets.

The wood component of the box is Ceylon or East Indian Satinwood (Chloroxylon swietenia), a hard, durable timber indigenous to Sri Lanka and long used for window and door frames, beams and columns in devales and temples erected in the Kandyan period. The box retains its original finely turned satinwood feet. These are button-like with unusually thin columns – a form more associated with the 17th century.

Parallels to the work on the box here abound:

The carving of the tortoiseshell has its antecedents in important ivory boxes and large ivory fans made in Kotte in Sri Lanka in the 16th century and now in European museum collections, demonstrating a continuity of motifs and skills in Sri Lanka from the 16th to the 17th centuries.

Ceylonese boxes and chests made entirely of ivory date to the period when the Portuguese were in Sri Lanka. The use of ivory veneer over a wooden substrate dates from the commencement of the Dutch period – so from around the mid-17th century.

Related boxes with pierced ivory over a wooden substrate dated to around the end of the 17th century are in the collection of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam – see one example. This example has similar carved and pierced scrollwork, pierced silver corner mounts, and similar handles with floral handle plates. The Rijksmuseum dates the box to c. 1690-1710. The same box is illustrated in Veenendaal (2014, p. 38) where it is dated 1650-1700.

A large portable shrine cabinet made entirely from ivory with similar pierced panels with small animals amid scrolling vines and attributed to the late 16th century, in a private collection and illustrated in Jordan-Gschwend & Lowe (2015, p. 151).

Several round ivory boxes, not pierced but with almost identical scrollwork and carved with traditionally clad Ceylonese human figures are known, all of which date to the mid-17th century. The Victorian & Albert Museum has one of these.

The work on the box here also is very similar to that on a small group of rare ivory cases made for Dutch clay pipes in the mid-17th century. One example now is in Singapore’s Asian Civilisations Museum. This example has beaded edging similar to that on the panels of the box here. Another similar pipe box in a private European collection is illustrated in Veenendaal (2014, p. 44). One other is in the Victoria & Albert Museum. These were very definitely made for the Dutch market – the Ceylonese were not tobacco users at the time.

Veenendaal (2014, p. 45) illustrates one small cabinet faced entirely with tortoiseshell thought to date to 1650-1700. It has silver mounts but the tortoiseshell is not carved or pierced.

Document and jewellery boxes carved in Sri Lanka from ebony and with similar, tight scrolling motifs are dated to as early as the 17th century. The type of work was known to the Dutch as custwerk – work made by carvers along India’s Coromandel Coast. Similar work was done in Sri Lanka and Batavia. Indeed, sometimes it is difficult to determine in which of these locations certain items were made because styles were copied but also because it is highly likely that skilled carvers migrated from one location to another. Wars and famine along the Coromandel Coast in the 17th century propelled emigration and it is likely that many Tamil artisans moved to Sri Lanka and Batavia as indentured workers.

Who were the carvers who worked on these exquisite boxes? The work was performed by highly skilled artisans divided according to caste groups which functioned as complex and highly segregated hereditary guilds. The system was administered or reinforced by the Kandyan government under the Kandyan king. Silver and goldsmiths were under the Badullu sub-caste, and ivory and horn carvers (which included tortoiseshell) were under the Liyana-waduwo sub-caste. Importantly, being in the same caste meant that ivory workers could also work in tortoiseshell and this explains the work on the box here being identical to that of ivory from the same period and now found in museums. The exclusivity given to these artisans was in exchange for land grants from the king and a requirement that they were expected to work as required for the king without charge.

The box here is in outstanding condition given its age and the materials from which it is made. There are some minor losses – some of the tortoiseshell pins used to hold the tortoiseshell panels to the wood base are no missing, as are some of the gilded silver studs. There is a small crack in the edging of the wood of the cover on one side and there is a chip to the underside of the wood of the cover on the other. No repairs have been made to the box and it is our judgement that none should be made. The condition does not warrant any interventions.

References

Brohier, R.L., Furniture of the Dutch Period in Ceylon, National Museum Board of Ceylon, 1978.

van Campen, J., & E. Hartkamp-Jonxis, Asian Splendour: Company Art in the Rijksmuseum, Walburg Pers, 2011.

Chong, A. (ed.), Christianity in Asia: Sacred Art and Visual Splendour, Asian Civilisations Museum, 2016.

Codrington, H.W., ‘The Kandyan Navandanno’, in The Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 21, no. 62, 1909.

Coomaraswamy, A.K., Mediaeval Sinhalese Art, Pantheon Books, 1956 reprint of the 1908 edition.

Jackson, A. & A. Jaffer, Encounters: The Meeting of Asia and Europe 1500-1800, V&A Publications, 2004.

Jaffer, A., Luxury Goods from India: The Art of the Indian Cabinet Maker, V&A Publications, 2002.

Jordan-Gschwend, A., & K.J.P. Lowe (eds.), The Global City: On the Streets of Renaissance Lisbon, Paul Holberton Publishing, 2015.

Lee, P. et al, Port Cities: Multicultural Emporiums of Asia 1500-1900, Asian Civilisations Museum, 2016.

Seipal, W. (ed.), Exotica: Portugals Entdeckungen im Spiegel furstlicher Kusnt – und Wunderkammern der Renaissance, Skira, 2000.

De Silva, P.H.D.H., A Catalogue of Antiquities and Other Cultural Objects from Sri Lanka (Ceylon) Abroad, National Museums of Sri Lanka, 1975.

Vassallo e Silva, N., et al, Stories of an Empire: Tavora Sequeira Pinto Collection, Museu do Oriente, 2022.

Veenendaal, J., Furniture from Indonesia, Sri Lanka and India During the Dutch Period, Foundation Volkenkundig Museum Nusantara, 1985.

Veenendaal, J., Asian Art and the Dutch Taste, Waanders Uitgevers Zwolle, 2014.