Enquiry about object: 6728

Historically Important Colonial Silver Standing Cup Relating to the British Conquest of Java, 1811, Inscribed & Dated

colonial silversmith either in India, probably Calcutta, or Batavia, East Indies. circa 1810

height: approximately 55cm, width: 38.5cm, depth: 26cm, weight: 5,550g

Provenance

Collection of Julian Sands (UK); previously sold at Sotheby's London, 1991.

This large, silver, museum-worthy standing cup and cover marks an important chapter in Southeast Asian history.

It is massive – it weighs more than 5.5 kilograms – and is of solid, high-grade silver, probably sterling silver. It was commissioned to mark a part of the 1811 British invasion of Java against the Dutch, under Gilbert-Elliot-Kynynmond, 1st Earl of Minto, which later saw Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles installed as Lieutenant-Governor of the Dutch East Indies.

The cup is of the highest quality. It was made either in India, probably Calcutta, where a number of colonial British silversmithing firms operated, or in Batavia, the Dutch East Indies, where there were a number of Dutch colonial silversmiths. In both locations, native silversmiths were employed in the workshops. (A similar, though less elaborate cup of the same period known as the Woutersen Cup, by the colonial Dutch Cape silversmith Willem Godfried Lotter, is illustrated in Heller, 1949, plate no. 2).

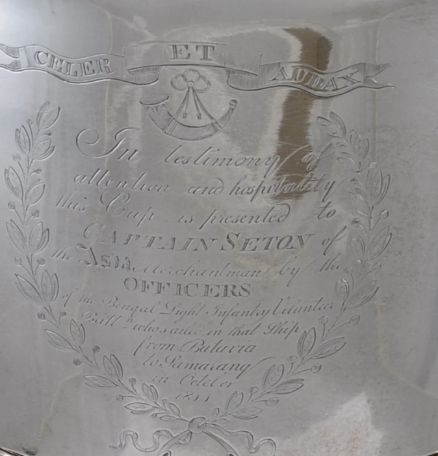

On one side, the cup is finely engraved with a ribbon, the motto ‘Celer et Audax’ (‘Swift and bold’), and a powder horn, beneath which is the inscription:

‘In testimony of attention and hospitality this cup is presented to Captain Seton of the Asia Merchantman by the Officers of the Bengal Light Infantry Volunteers Battn who sailed in that ship from Batavia to Samarang [Semarang] in October 1811.’

The cup is beautifully engraved on the other side with a sailing ship at sea surrounded by a laurel border and above a ribbon and flowers. The ship clearly is marked ‘Asia’ on it stern.

Each side of the cup is decorated with applied bifurcated and entwined snakes which serve as handles. The domed cover is surmounted by a finial formed as a pine-cone or fruit emerging from leaves.

The foot is wide and domed. The foot, base of the body, upper rim, and crest of the lid are all finely chased with acanthus leaf borders.

The body of the cup is extensively engraved.

The foot is attached to the base via a bayonet fitting. There is a detachable foliate girdle. Colonial silversmiths in Calcutta tended to use British silversmithing techniques and the use of a bayonet fitting is unusual in British silversmithing. It might be more common in Dutch and Dutch colonial silversmithing which would suggest that the cup was made in Batavia rather than Calcutta. But then the snake handles are more typically colonial Indian.

The cup is in excellent condition. There are no maker’s or assay marks as befitting its colonial origins. The cup is of monumental proportions but even allowing for this, is heavy for its size. Not only is this cup historically important, but by any measure, it is an outstanding example of of the silversmith’s craft.

Captain Seton & the Invasion of Java

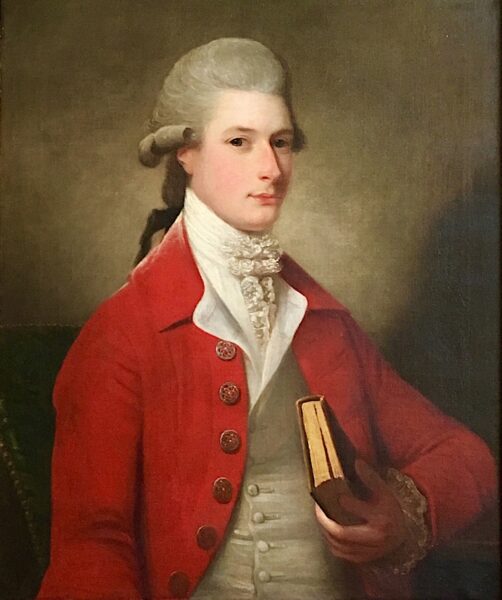

The Captain Seton referred to here is either of two men: Archibald Seton (1758-1818), a Scot who served the East India Company (EIC) as a colonial administrator, Resident and civil servant. He first served the EIC in Bengal and then in positions in the Districts of Bhangolpore and Behar. Or George Seton, who was also in Penang around the same time and who is believed to have been a sea captain for the EIC, but about whom not much is known.

In 1806, Archibald Seton was appointed as Resident at the Court of Shah Alam II, at Delhi in 1806, and after Alam’s death to that of his successor, Akbar Shah II, the penultimate Mughal ruler. Seton’s time in Delhi coincided with the East India Company’s consolidation of its rule over the remaining parts of the disintegrating Mughal Empire. The EIC dispensed with ruling in the name of the Mughal emperor and eventually exiled the ruler. Prior to that, the EIC exiled Akbar Shah II’s preferred choice of heir, Mirza Jahangir, after he fired a rifle at Seton in Delhi’s Red Fort. Seton, writes William Dalrymple in The Last Mughal, was backing another candidate, which irritated Mirza Jahangir and led him to taking a shot. He succeeded only in blowing off Seton’s hat (Dalrymple, p. 47).

On 9 May 1811, Seton was appointed Governor of Prince of Wales Island (present-day Penang in Malaysia). Seton was in the colony only briefly when he joined the invasion of Java. The invasion o took place between August and September 1811 during the Napoleonic Wars. Originally established as a colony of the Dutch Republic, Java remained in Dutch hands throughout the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, during which time the French invaded the Dutch Republic and established the Batavian Republic in 1795, and the Kingdom of Holland in 1806. The Kingdom of Holland was annexed to the First French Empire in 1810, and Java became a de facto French colony, though it continued to be administered and defended primarily by Dutch personnel.

The British invasion of Java took a total of forty-five days, during which Raffles was appointed the Lieutenant-Governor of the Dutch East Indies by Minto before hostilities formally ceased. He took his residence at Buitenzorg (Bogor) and despite having a small subset of Britons as his senior staff, kept many of the Dutch civil servants in the governmental structure.

The British invasion took place with regiments brought in from India, including troops from the Bengal Light Infantry Volunteers Battalion (the Battalion that presented this cup), although several ships were lost in a storm on the voyage from India. Troops landed on Java on 4 August, and by 8 August the undefended city of Batavia was taken. The Dutch, French regulars and native militiamen defenders withdrew to Fort Cornelis, which the British besieged, and captured on 26 August. General Janssens, the Dutch Governor General, withdrew to Semarang on September 1. A series of amphibious and land assaults captured most of the remaining strongholds, and the official capitulation of the island to the British occurred on 18 September. Janssens and other Dutch officials attended a meeting with Lord Minto on September 24, thereafter the victorious British held a celebratory ‘ball and supper’ party which the senior Dutch officials attended before being allowed to leave for Holland.

Thereafter, the British secured the island by installing regiments in strategic locations. Sending officers and troops of the Bengal Light Infantry Volunteers Battalion from Batavia to Semarang, an important port on the north coast Java where the Dutch had also stationed troops, was a prelude to Raffles’ assault on Yogyakarta on 21 June 1812. Yogyakarta was one of the two most powerful indigenous sultanates in Java. During the attack, the Yogyakarta palace or kraton was damaged badly and looted by British troops. Raffles seized much of the contents of the court archive. Many of the manuscripts taken today are in the British Library.

Other than the assault on Yogyakarta, the relative lack of disruption caused by the British to much of Java and particularly to Batavia suggests that many Dutch-owned businesses were allowed to remain operating, so it is not out of the question that this cup was commissioned from a Batavian silversmith rather than being imported from Calcutta.

Britain returned Java to the newly independent United Kingdom of the Netherlands under the terms of the Convention of London in 1814. One enduring legacy of British rule on Java was that the British decreed that traffic should drive on the left, a practice that remained on Java and Indonesia more widely to this day.

Archibald Seton

References

Dalrymple, W., The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi, 1857, Bloomsbury, 2006.

Gans, M.H., & Th. M. Duyvene de Wit-Klinkhamer, Dutch Silver, Faber & Faber, 1961.

Harfield, A., ‘Cavalry units in Java 1811-16’, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Autumn, 2003.

Heller, D., A History of Cape Silver 1700-1870, David Heller (Pty) Limited, 1949.

Voskuil-Groenewegen, S.M. et al, Zilver uit de tijd van de Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, Waanders Uitgevers, 1998.

Wilkinson, W.R.T, Indian Colonial Silver: European Silversmiths in India (1790-1860) and their Marks, Argent Press, 1973.