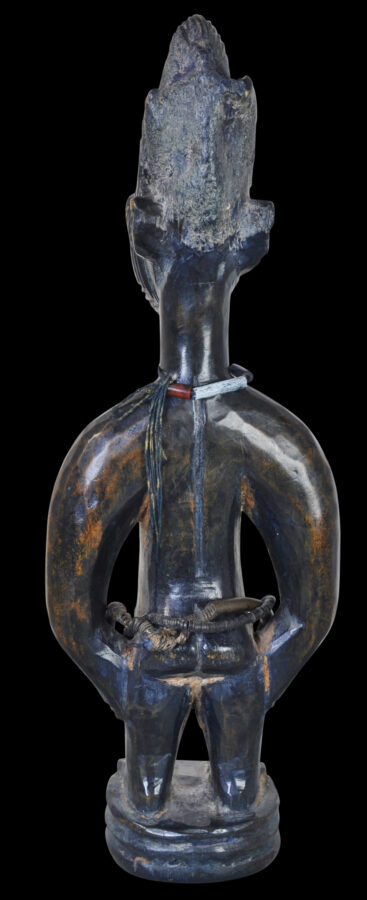

This pair of ibeji figures (ibeji means ‘born two’) stands with their hands on their hips and with elongated arms and short legs. Typically, their heads are over-sized – one-third the size of their bodies – because for the Yoruba, the head is where the spirit resides. Both are darkened from years of having been rubbed with dark oil. They also have a blue hue – blue pigmentation has been added to the oil. They have worn features from age and much handling and caressing – from this their age and authenticity is clearly evident.

One is a male and the other a female. The two are not twins but clearly are by the same carver. It is likely that they were considered siblings rather than twins.

Their tall blue coiffures are decorated with braids at the top. They have prominent, pursed lips, fine ears and broad noses. Their almond-shaped eyes are wide and bulging.

Two sets of vertical scarification are on their cheeks and the forehead of one, and then each has further, prominent scarification down the sides of the face.

Both have strings of fine coconut shell disks around their waists. The female figure also has a string of exceptionally fine brass disks around the waist and a necklace of trade beads.

Rekitts Blue, much used in the 19th century and early 20th century, has been applied to the bodies and hair of both. (Rekitts Blue was a washing soda coloured with a blue aniline dye and was widely used as a source of blue pigment in many tribal societies from South American Indians, across Africa, and to the aboriginal people of Australia.)

Each stands on a circular platform.

As with all ibeji figures, these two are carved as adults, which is common in African sculpture. Though meant to represent children, their features are more mature, including scarifications on the face, ample carved pubic hair, full pointy breasts on the female, and a prominent penis on the male.

Usually, ibeji figures are carved as twins.

Why is twin depiction so prevalent in Yoruba art forms? Giving birth to twins is common among the Yoruba. In fact, they are believed to have the highest dizygotic (non-identical) twinning rate in the world. The births of twins amongst Yoruba women are four times more prevalent than anywhere else in the world.

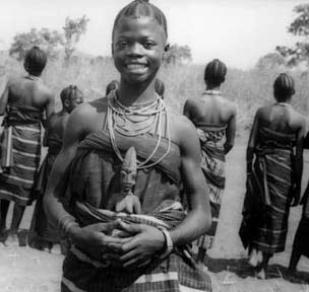

The Yoruba believe that twins share the one soul. If one twin dies, the balance of the soul will be troubled. Due to high infant mortality, ibeji figures were carved as spiritual representations of the dead twins. These figures were commissioned from village carvers. Usually they were placed in the living area of the house and fed, bathed and dressed regularly. (The practice is not unlike the treatment of images of Hindu gods in Hindu households in India.) These figures are particularly special to the mother, who keeps them close to her and caresses them in a loving manner. Rituals and prayers are performed for the child’s birthday and other celebrations or festivals.

Traditionally, the parents would visit a priest called a babalawo to determine the wishes of the deceased twin or twins. Special names were given to each twin. The first twin is often named Taiyewo or Tayewo which means ‘the first to taste the world’, names which are often shortened to Taiwo, Taiye or Taye. The last born twin traditionally is named Kehinde.

The Yoruba believed that Kehinde sends Taiyewo to find out what life is like on earth and in this way Taiyewo becomes the first child to be born. Taiyewo then communicates with Kehinde via his cries, explaining whether life is likely to be good or not. If Taiyewo determines that it will not be good then both of them will return from where they have come. Kehinde is considered the true elder of the twins despite being the last to be born. Kehinde is referred to as Omokehindegbegbon, ‘the eldest child who came last’, because of the privilege of sending Taiyewo on an errand. On the other hand, Taiyewo is referred to as Omotaiyelolu, ‘the child who first came to taste life’.

In this way, the ibeji twins here are representations of Kehinde and Taiyewo, proxies for them and the means by which their soul can be appeased.

The ibeji figures here are not twins but likely to be siblings, but the belief notions are likely to be the same.

Today, the Yoruba people form one of the largest tribes in west Africa. They number around 30 million and are predominant in Nigeria where they comprise 21 per cent of the population. Most Yoruba speak the Yoruba language. Today, 60 per cent are Christians and another 30 per cent are Muslims. But many, especially in rural areas, still practise old Yoruba traditions such as those based around ifa and orisha ibeji (twin worship).

The ibeji figures here are in fine condition and have clear age. There is what is likely to be some old termite damage to the backs of both coiffures (but the oiling and caressing continued long after this occurred, so that the dame itself has wear and patina.) Also, one of the breasts of the female figure is foreshortened but this loss too has ample wear and patina.

References

Bacquart, J. B., The Tribal Arts of Africa, Thames & Hudson, 1998.

Fagg, W. & Pemberton, J. III., Yoruba: Sculpture of West Africa, Collins, 1982.

Rowland, A., Drewal, H. J. & Pemberton, J. III., Yoruba: Art and Aesthetics, Museum Rietberg, Zurich, 1991.