Enquiry about object: 6846

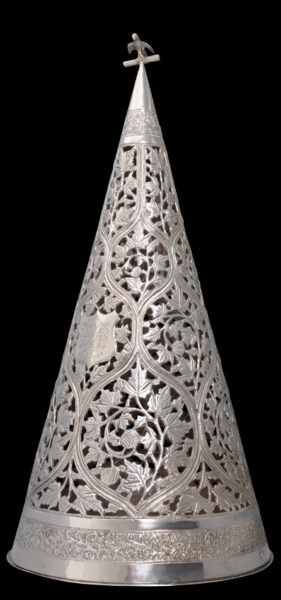

Parsi Ritual Silver Ses or Sace Cone (Soparo)

Northern India dated 1933

diameter: 17.3cm, height: 34.5cm, weight: 787g

Provenance

UK art market

This unusually tall pierced, cone in high-grade, almost pure silver known as a soparo was used on a Parsi ses tray to hold lumps of rock sugar or a type of flat sugar round known as patasa and to allegorically represent Mount Hara, the mountain of sweetness. The soparo often was left empty and its presence on the ses was symbolic.

A sace or ses tray held various ceremonial utensils and items of symbolic importance used during a Parsi or Zoroastrian ceremony. The utensils and items placed on the try would vary depending on the occasion.

This example of a soparo was almost certainly made in Kashmir, northern India, or made elsewhere but by a Kashmiri silversmith. Its sides are pierced and engraved with chinar or plane tree leaves, stems and nuts all in a trellis form. The top and bottom of the cone have borders engraved with the coriander leaf and flower motif. The work and these motifs is typically Kashmiri.

An armorial shield is engraved with the overlapping initials of the Parsi individual who either commissioned or was presented with the cone and a date: 27-2-1933.

The top pf the cone is mounted by a solid-cast silver dove.

The base fits into the cone with a bayonet fitting and is fitted with a rectangular silver handle. It is impressed with a maker’s mark ‘K.H.’ and ’94’ suggesting that the silver content is 94% compared with the sterling grade of 92.5%.

The Parsis (or Parsees) subscribe to Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest living religions. It is said to have its origins with Darius, who was crowned king of Persia in 522 BC, and was the first of the Achaemenid kings to be confirmed as a true follower of Zoroaster. Ahura Mazda, proclaimed by Zoroaster as God, was mentioned and celebrated as Creator in many of Darius’ speeches.

For the Parsis, and in the Zoroastrian scriptures of the Avesta, Mount Hara is the source of all mountains of the world; all other mountains and ranges are lateral projections that originate at Mount Hara.

Today, probably there are fewer than 125,000 Parsis or Zoroastrians worldwide. Many fled Persia to avoid religious persecution and were welcomed in Bombay, India, which today has the world’s largest concentrations of Parsis, but perhaps no more than 80,000 live in Mumbai/Bombay, a city of 14 million people, and no more than 6,000 live in Karachi in Pakistan.

Like the Chinese of Southeast Asia, the Parsis of India and Pakistan are a distinct but exceptionally successful commercial minority. By the nineteenth century, Bombay’s Parsi families dominated the city’s commercial sector, particularly in spinning and dyeing and banking.

Wealth from these activities was put into property so that by 1855, it was estimated that Parsi families owned about half of the island of Bombay. Today, India’s most prominent Parsi family is the Tata Family, founders and owners of India’s most prominent conglomerate the Tata Group.

Well off though they are as a community, the Parsis are dying out. It has been estimated that a thousand Parsi die each year in Mumbai, but only 300-400 are born. Today, one in five Mumbai Parsis is aged 65 or more. In 1901 the figure was one in fifty. Low birth rates are the main factor.

Nonetheless, many vestiges of the Parsis’ contribution to commerce in South and East Asia remain. Apart from India’s giant Tata Group, smaller examples can be seen: small change offices in Hong Kong are known locally as ‘schroffs’ after a common Parsi surname, and in Singapore the road that runs alongside that country’s finance ministry is known as Parsi Road.

The soparo cone here is in excellent condition. Other (smaller) examples are illustrated in Stewart (2013, p. 206) and Rai & Mani (2017, p. 241).

References

Dehejia, V., Delight in Design: Indian Silver for the Raj, Mapin, 2008.

Godrej, P.J. & F. Punthakey Mistree, A Zoroastrian Tapestry: Art, Religion & Culture, Mapin Publishing, 2002.

Rai, R., & A. Mani, Singapore Indian Heritage, Indian Heritage Centre, 2017.

Stewart, S. (ed.), The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination, SOAS, 2013.