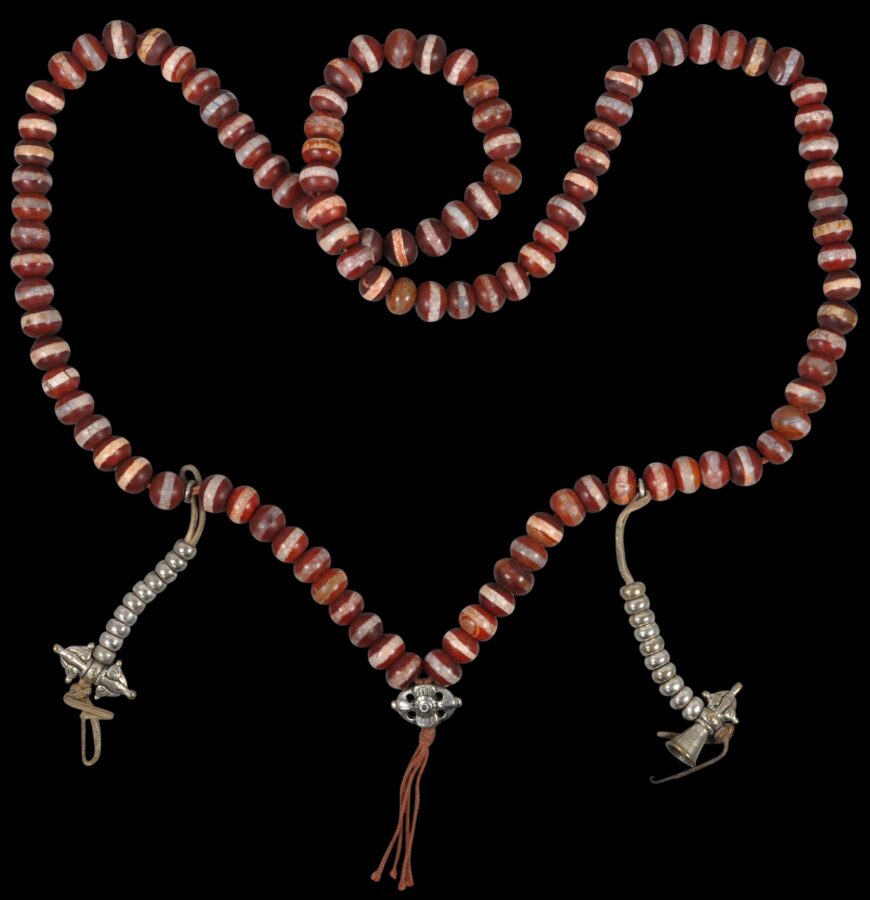

This very rare Tibetan mala of 108 ancient etched beads plus silver counter beads and solid-cast silver terminals is in the form of two double vajras and a ritual bell (ghanta).

The beads are exceptional and ancient. Tan (2015, p. 119) identifies beads of this type as coming from the Samon River Valley located south of Mandalay in Upper Burma. This area was settled around the same time as when Pyu culture evolved in Burma, around 200BC.

Each bead is of hand-cut, hand-drilled and hand-polished carnelian and has a broad white band running around its middle. The band was achieved by applying heat and sodium carbonate to the surface of the bead. The process did not etch the beads as such but rather caused micro fractures of the carnelian so that the surface appears white. It was a technique probably first used by bead makers in the Indus Valley. Decorating carnelian beads in this way transformed them into highly valued trade goods, and their spread helped to disseminate the bead decorating technique to other cultures such as bead makers in Burma. Those cultures that did not develop the technique relied on imported beads. The Tibetans are an example, who regarded such beads as a type of Phum Dzi bead with talismanic properties. Often such beads were already ancient before they reached Tibet with their antiquity further enhancing their talismanic (and thus their commercial) value in the mindsof the Tibetans.

Pyu was a group of city-states that existed from around 200BC to 1100AD in the area that is now present-day Upper Burma (Myanmar). The cities were trade focused and Chinese records from the 9th century evoke a sophisticated culture with sumptuous courts and richly adorned Buddhist monasteries.

The city-states – there were five major walled cities in total plus some smaller towns – were located along an overland trade route between China and India. In these, the Pyu pioneered urban development in Southeast Asia and were masters in brickmaking, ironworking and water management (Guy, 2014, p. 68).

Pyu culture was heavily influenced by trade with India. Buddhism was imported along with other cultural and political ideas. Pyu civilisation largely ended in the 9th century when the city-states were destroyed by repeated invasions from the Kingdom of Nanzhao. Pyu settlements remained in Upper Burma for the next three centuries but gradually these were absorbed into the expanding Pagan Kingdom, and ultimately, the Pyu assumed Burman ethnicity.

The trading nature of the Pyu means that Pyu gold beads have been found as far afield as Thailand, Vietnam and China.

Buddhist rosaries evolved from ancient Hindu-Indian mala prayer beads. In Tibet, they were used by both laymen and monks. Generally, they comprise 108 beads – sometimes more and sometimes less depending on the personal mantras followed by the user, plus others that served as counters or markers. The beads were used to count repetitions of prayers.

The mala here is string on leather cord. The silver used to cast the three silver finials and the counter beads is close to pure. The mala is a superb example.

References

Allen, J., ‘Tibetan zi beads’, in Arts of Asia, July-August 2002.

Green, A., & T.R. Blurton (eds.), Burma: Art and Archaeology, The British Museum Press, 2002.

Guy, J., Lost Kingdoms: Hindu Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014.

Sherr Dubin, L., The Worldwide History of Beads, Thames & Hudson, 2009.

Tan, T., Ancient Jewellery of Myanmar: From Prehistory to Pyu Period, Mudon Sar Pae Publishing House, 2015.