This very rare and complete suite of Zanzibar-Omani bridal jewellery is of silver with applied gold plaques and traditional red trade glass beads. The set tells much about Zanzibar’s relationship with Oman, and its relative wealth from trade.

It is also the only such set we know of currently available on the market.

It comprises five separate components: a headdress, a pair of matched temporals with ear ornaments called kharam or sils, a large khatma necklace incorporating a hirz box, and a shigbat to be worn beneath the chin.

The set is matched. Its opulence suggests it is of high status. The elements are coated in scented sandalwood paste, which was done as a part of the wedding rituals. We have not sought to remove this – it is an important element of the story of this set.

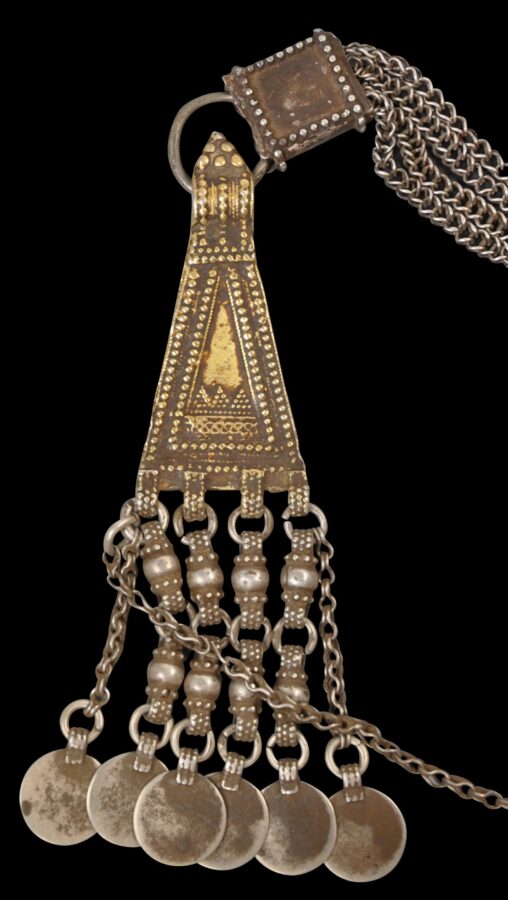

The headdress comprises a band of four silver chains linked between two silver boxes from which two triangular elements are suspended. The fronts of these elements are wrapped with gold sheet impressed with triangle, granulation and other motifs. From these are suspended six silver bead chains with terminals of plain silver disks. The elements are then linked to one another by means of a single silver chain.

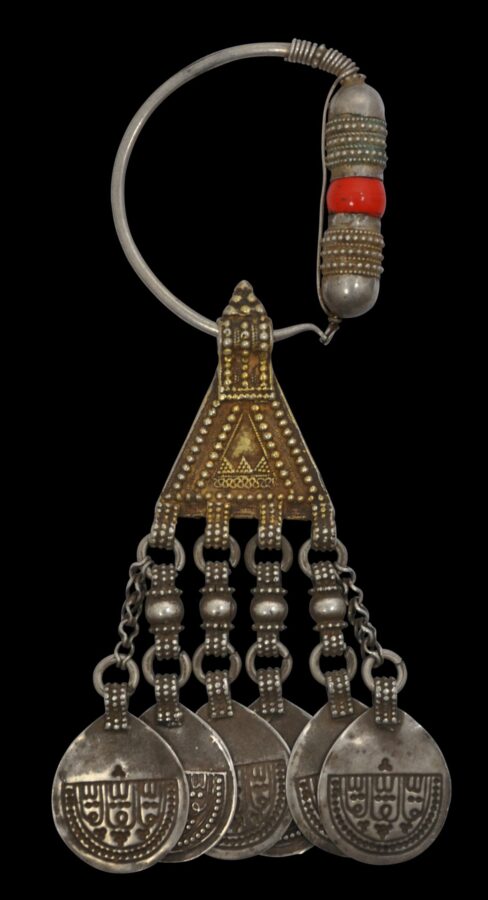

Next are the temporals with ear ornaments (kharam or sils). The temporals comprise large silver hoops decorated with silver beads with ‘thorny’ bands and separated by red coral beads. Triangular elements, again wrapped with embossed gold sheet, are suspended from these, and from each of these are suspended six coin-like pendants via chains and spherical silver beads. These are embossed with strange motifs suggesting a Zanzibar provenance.

Importantly, the triangular gold elements on the headdress are a precise match with those on the temporals, demonstrating that this is a cohesive set.

The next item is a khatma necklace with a hirz amulet box. This is a particularly opulent ensemble; indeed it is unusually grand and more elaborate than even the best examples of similar boxes from Oman. The box is suspended from a rod known as an amud that is decorated with pink glass or ceramic beads that alternate with gold-wrapped hoops attached to the top of the hirz box. There is also a large central bead that is wrapped in gold. The length of the amud is such that additional side panels wrapped in embossed gold sheet decorate each side of the hirz box. The side panels are embossed with a gold cash or coin motif. Such a motif is not seen in Omani jewellery but is more likely among Zanzibar jewellery given Zanzibar’s trading entrepot role.

The rare addition of these gold-wrapped side panels is to further demonstrate the wealth and status of the wearer.

The front of the box is decorated with a large panel of embossed sheet gold. Such a large gold sheet is unusual for such boxes and possibly this suggests a Zanzibar rather than an Oman provenance.

A fringe of eleven pairs of heavy silver chains that terminate with square sheet silver terminals with red barrel bead spacers is suspended from the base of the hirz box.

The box itself is suspended from a thick twisted cotton cord that links on each side to four strands of silver beads.

Finally, the shigbat or shubqah pendant comprises a stiff panel of embossed gold-wrapped plaques interspersed with ‘spiky’ silver beads and red barrel beads suspended from two bands of silver chains and gold-wrapped spreaders. Such a pendant was not worn conventionally on the chest as such, but just beneath the chin to cover the neck, and suspended from the headdress chains.

The applied gold sheet segments on the shigbat almost certainly were imported from India or made using a die from India. Each square-shaped element features an image of the Hindu deity Hanuman. Such a foreign element is to underscore the high status of the wearer, but so as not to deny the Islamic faith of the wearer, each plaque has been set with the Hanuman figure upside down or on an angle.

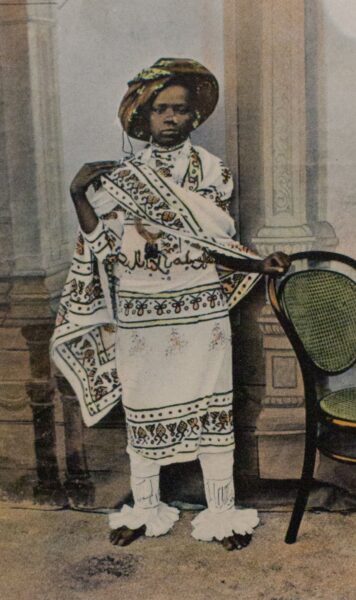

The coin-like pendants that are suspended from the ear ornaments are embossed with strange motifs that suggest a Zanzibar rather than an Omani provenance. The series of dots is not unlike that often seen on Lamu and other Swahili Coast ear ornaments, anklets and so on. The swirling lines also seem to be stylised versions of the swirling insignia used by Said bin Sultan (b. 1791-1856), the Sultan of Muscat and Oman who moved the court from Muscat to Zanzibar, or might be based on the swirling Arabic script used on some Zanzibar coins issued in the early 20th century. Swirling motifs that possibly relate also were used on the textiles worn by Swahili women, as evidenced by the image below, drawn from an early Zanzibar postcard.

Above: An image of a Swahili woman taken from an early Zanzibar postcard. Her dress is decorated with swirls and curling motifs.

Zanzibar provenance of the suite also is suggested by its relative opulence: Zanzibari pieces are likely to be decorated with more gold than Omani equivalents on account of Zanzibar’s relative prosperity and also because of Zanzibar’s relative splendour being the seat of the relocated court.

These coin-like pendants are known on only a handful of Zanzibar-Oman jewellery items (probably less than five known examples). Sometimes they are attributed to ‘Zanzibar or Sur’ in Oman. Linking these to Sur is not surprising – Sur is a coastal town in Oman, the main town for shipbuilding, and the main port that connected Oman with Zanzibar. If such ornaments were made in Zanzibar, then it is likely that some would have found their way to Sur. Forster (1998, p,. 56) illustrates a pair of ear ornaments with similar pendant medallions or ‘circular hangers’ and observes that the hangers are ‘most unusual’. Perhaps, it is because possibly they are not from Oman but were imported.

Zanzibar was at first ruled as an effective colony of the sultans of Oman but as the island became wealthier because of the trade in ivory, gold, spices, timber and slaves, the Omani court relocated to this new commercial centre of dominions. Over time, Oman grew relatively impoverished and an administrative after-thought whilst Zanzibar continued to prosper. In a sense, Oman almost was ruled as a colony of Zanzibar. This shift in commercial and political power was reflected in the jewellery and other arts. The jewellery of the Arab population of Zanzibar was essentially Omani but with some local twists. It is likely that silver and goldsmiths operated in Zanzibar – it would have been surprising if this was not the case given the growing wealth of its commercial trading elite and the fact that the Oman court had relocated there. These smiths seemed to have made jewellery in the Omani tradition but with some local augmentation, or modified jewellery that had been produced in Oman, to suit local tastes. The island’s ethnic make-up was diverse and so other influences are likely to have made their impact on local material culture including jewellery design. Quite apart from expatriate Omanis and other Arabs who resided in Zanzibar, there were the local Swahili Africans, but also a rich mix of other trading groups such as Parsis, Indian Khojas and Bhoras, Hindu Indians, Christian Goans and Ceylonese.

The set here is in excellent condition. There are no obvious losses are repairs. The set is evocative and museum-worthy.

References

Dale, G., The Peoples of Zanzibar: Their Customs and Religious Beliefs, The Universities’ Mission to Central Africa, 1920.

Forster, A., Disappearing Treasures of Oman, Archway Books, 1998.

Meier, P. & A. Pupura (eds.), World on the Horizon: Swahili Arts Across the Indian Ocean, Krannert Art Museum/Kinkead Pavilion, 2017.

Norris, M., & P. Shelton, Oman Adorned: A Portrait in Silver, Apex Publishing, 1997.

Rajab, J.S., Silver Jewellery of Oman, Tareq Rajab Museum, 1998.