Some Observations on the Basics of Religion & Art in Japan

Japan’s two main religions, Shintoism and Buddhism, have often been uneasy bedfellows.

Shintoism is Japan’s home-grown religion, and with its emphasis on the spirits of the natural world if anything has some similarities to Daoism traditionally practiced in China and by many Chinese in Southeast Asia even today. Buddhism however was a direct import from China.

Buddhism offered a radically different set of beliefs from those previously held – not least its offer of a concept of salvation that was better defined rather than the nebulous, unappealing eternity of an underworld. Shinto was very much concerned with reverence for spirits and placating them. Buddhism however, introduced the notion of karma thus bringing the focus back to the individual and how they might lead a meritorious life with rewards that essentially, they could win for themselves.

Over the centuries, the two religions became entwined and grafted on to each other with adherents broadly following one strand or the other but a blend nevertheless. One early empress decreed that large copper images of the Buddha should be made but also that the Shinto gods of heaven and earth should not be neglected either. This was typical of the compromise which emerged.

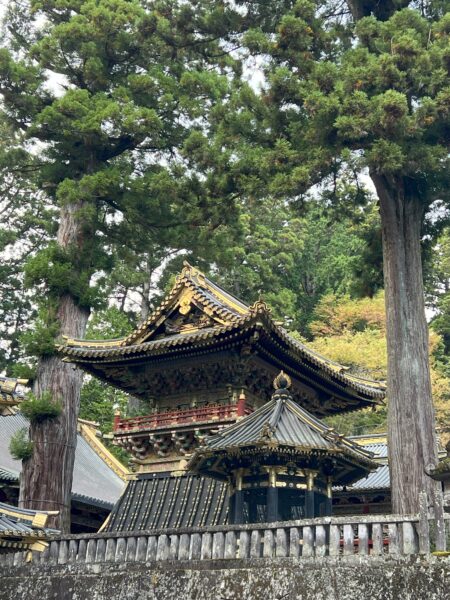

Buddhism replaced burial as the preferred means of body disposal with cremation and so the traditional practice of creating giant burial mounds (tsuka) in respect of royalty and aristocrats fell out of fashion. The effort and capital that went into burial mounds was redirected to the construction of elaborate Buddhist temples often with fabulously intricate, gilded wooden carved features. These temples were based largely on Tang Chinese prototypes.

From here, Japanese temple facades and domestic interior design barely changed. For instance, the later Song dynasty in China introduced the chair to the Chinese household. But in Japan, the fashion for architecture and interiors still rested on Tang practice and aesthetics. The Japanese continued to sit on the floor as they had in Tang times. The floors were covered in fine matting of woven rice stalks known as tatami. But in China, furniture continued to evolve and became quite elaborate.

Above: sitting on a tatami-covered floor to eat. Traditional Japanese interiors did not change from Tang times.

Similarly, the costume of the Japanese geisha barely evolved beyond that worn by Tang Chinese princesses such that if you want to know how a Tang princess dressed in China – just look at the Japanese geisha dress – the elaborate silks to the high coiffures all have Tang precedents.

Governance in Japan became diffuse and practical political power eked away from the emperor. All orders and commands were given in the emperor’s name but true power resided with those able to gain that particular stamp of approval. This is what the Samurai houses essentially fought over – not the wellspring of power itself but the ability to access it and use it for themselves. Various shogunate would rule Japan (or parts of it) in the emperor’s name but in truth, the emperor was largely sidelined, though remained at the top of the hierarchy in nominal terms, and was still viewed as divine.

Interactions with Europeans threatened this system of Japanese compromise. Buddhism was accommodated when it arrived in Japan but Christianity was not. Europeans including merchants were seen as proselytizing on behalf of their religion and so in need of containment. Catholicism was headed by the Pope – a potential rival power source to the Japanese emperor and his divinity.

In 1634, European traders were restricted to Dejima, an island in Nagasaki harbour. Mostly, they were Dutchmen who had protested to the shogun that as Protestants, they were not subject to the rule of the Pope as Catholics were. Most other Europeans gave up on the Japan trade and so the Protestant Dutch thereafter largely had it to themselves.

It became necessary to detect those Japanese who had converted to Christianity. An unusual device developed – cast bronze fumi-e or ‘trampling images’. These were cast with images of Christ that Japanese subjects were required to walk on to prove that they had no allegiance to Christianity.

The Dutch, being Protestants, generally had little problem with trampling on a fumi-e image in order to secure trade deals. Japanese Catholic converts on the other hand often were unable to dishonour images of Christ in this way and so went to their deaths.

Buddhist temples became centres of this type of enforcement and local populations were made to line up and walk over fumi-e images in the temple to prove they were true Buddhists.

Ultimately, it was not until 1871 that Christianity was legalised as part of the Meiji Restoration reforms.

The shogunate system and the culture of the Samurai came to dominate Japan. Even hairstyles reflected the Samurai look. Traditionally the Samurai shaved the front of their head so that their helmets would fit more securely. Such a hairstyle then became a statement of commitment. The chonmage (‘cut-and-knot’) style became the fashion and this was reflected even in Japanese woodcuts.

Artists such as Hokusai and Hiroshige are well known today but the woodcarvers who took their designs and reproduced them accurately on blocks of wood also deserve attention. They would carve out each part of each image on a separate block depending on the colour it was to be, so that a picture of say five different colours needed five different blocks – each with a part of the overall image. In any event, it was woodcut artists who recorded preoccupations under Shogunate rule in Japan.

The Meiji Restoration in 1868 sought to restore the active political power of the emperor thereby ending the period of family-based, regional Shogunate/Samurai rule. The emperor was also seen as the embodiment of Shintoism. Consequently, there was a violent decoupling of Shintoism from Buddhism and a desire to restore the ‘purity’ of Shintoism from the imported belief system of Buddhism. This led to the destruction of some Buddhist temples and monasteries.

Ironically, there was also a desire to modernise, and so a Japanese mission in 1871 went to Europe to ‘cherry pick’ the best aspects of European practice to import to Japan – the French legal system, the British navy, the German army, and the Prussian education system all became models for Japan’s modernisation. Even today, the uniforms of Japanese school children still feature Prussian military jackets for boys, and Victorian sailor suits for girls.

With the Meiji Restoration, many Samurai families became impoverished and so their weapons and art holdings were available at knock-down prices in Japan. Western collectors and dealers were able to buy them and take them back to London, Paris and so on and this triggered the fashion for Japonisme in European design.

Today, most Japanese who profess to follow any religion would say that they are Shinto, but Buddhism still has significant influence. The shrines and monasteries of both throve but largely because of their investments and their tax-free status.

One practical impact of Shintoism can be found in how Japan has investigated its archaeological history. Traditionally, a Japanese emperor stays away from funerals except for those of their own parents because of a cultural belief based in the Shinto religion that considers death impure. Additionally, the Imperial Household Agency is responsible for the oversight of 900 tombs and mounds in around 450 locations. The Agency does not permit archaeological digging around the mounds which would be seen as disrespectful and also a gross disturbance and potentially calamitous of the resident spirits, Accordingly, developments in the understanding of Japan’s past has been held back by this Shinto-inspired desire to leave burial mounds untouched compared with China where there are no such cultural constraints on disturbing burial mounds.

Above: The Kinkakuji temple of the Zen Buddhist sect. Built near Kyoto, 15th century.

Above: Torii gates – a Shinto device to mark the boundary between the everyday world and the world inhabited by spirits. Near Kyoto.

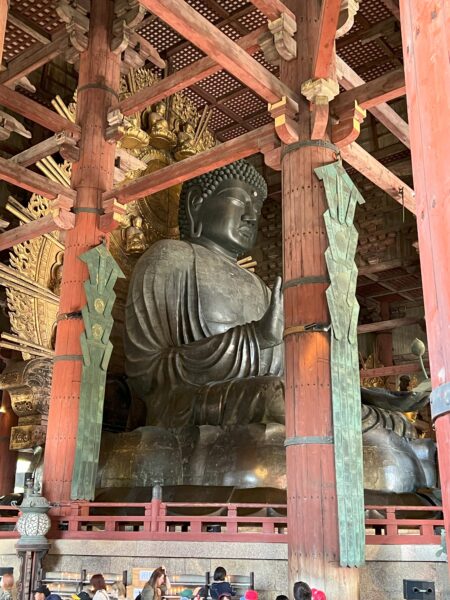

Above: A massive image of Buddha, Nara.

Above: Tang-inspired architecture, part of the Buddhist Toshogu temple near Nikko.

Above: Shitennoji Temple, Osaka, one of Japan’s oldest Buddhist temples.

____________

Receive our regular catalogues of new stock, provenanced from old UK collections & related sources.

See our entire catalogue of available items with full search function.

______________