Colonial Spain & Portugal – Conduits for Motif Exchange from Asia to the Americas

Among Europeans, the Spanish and the Portuguese have perhaps the longest histories of interacting directly with the peoples of East Asia. The Philippines, East Timor, Malacca in Malaysia, Goa in India, coastal Sri Lanka and Macau were among the regions under Spanish or Portuguese control from the 16th century onwards. And with Asia. The integration of the Philippines with Mexico perhaps was the most overt example. It is not widely known, but from the 16th through to the early 19th century, the Philippines was not ruled directly by Spain but actually administered from Mexico.

Spain and Portugal’s conquest of America and parts of Asia in the 16th century was complemented by the establishment of additional trading outposts elsewhere. For example, the Portuguese first established a presence in the then Siamese capital Ayutthaya during the reign of Ramathibodi II in 1511 AD. They brought with them Christianity and technical prowess in canal building and surveying. The Siamese King allowed them to settle outside the capital in the Samphaolom sub-district. (The Thai Government registered the site as a National Monument in 1938. Excavated objects such as Jesuit porcelain fragments and crucifixes are on display in Bangkok’s National Museum today.)

The New World provided Spain and Portugal with immense wealth – massive new sources of gold and silver directly increased wealth but also allowed global trade to increase – effectively the world’s money supply greatly increased with all the new bullion. This expansion in the global money supply allowed global trade to expand exponentially. The gold and silver was sent to Europe but it also circulated to Spain and Portugal’s other newly established colonies in India and East Asia.

Above: A carved ivory figure of the Crucified Jesus, Portuguese Goa, India, 17th-18th century. Sold by Michael Backman Ltd to the Musee des Arts Decoratifs de l’ocean Indien, Reunion, France.

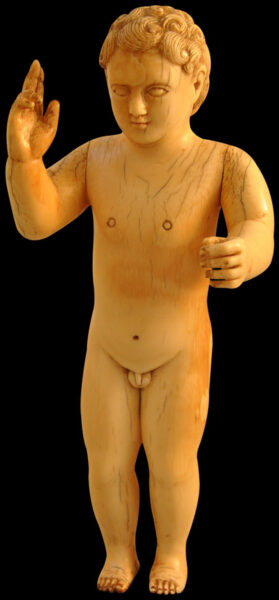

Gems, ivory, tropical timbers, and tortoiseshell also were among the newly accessed commodities. The indigenous peoples of Portugal and Spain’s new dominions received Christianity in return. This had a profound impact on their art, plus it lead to new forms of trade: Goa and Ceylon became important centres for Christian art with the manufacture of carved ivory Holy Family figures and saints – items that were then traded across the Portuguese and Spanish empires from Mexico to the Philippines. New techniques were introduced too. Silver and gold filigree work was already being produced on the Iberian peninsula but now Spain and Portugal placed orders for this type of work among indigenous artisans.

Above: A carved ivory figure of the infant Jesus (Salvator Mundi), Portuguese Goa, India, late 17th century. Sold by Michael Backman Ltd to the National Gallery of Australia.

Above: A reverse-glass painted image of the Crucified Christ, southern China, circa 1760. Sold by Michael Backman Ltd to the Musee des Arts Decoratifs de l’ocean Indien, Reunion, France.

The Jesuits were important too. They commissioned religious artworks in these new locations for export to their churches and monasteries elsewhere. Jesuit-themed porcelain was commissioned from China via Macau for example and from there it found its way to Portugal, South America, India and the Philippines.

Trade between the colonies was important. In this way 16th century Asia had close commercial links with South America, demonstrating that globalisation is hardly a new phenomenon. As mentioned, an important example was the trade links that developed between Mexico and the Philippines. These developed 400 years ago and lasted for a 250-year period when a small fleet of Spanish ships known in Mexico as the Nao de la China sailed the 9,000 nautical mile journey between the two – the so-called Galleon Trade. Goods were traded directly by this means but also from other locations such as India, China, Japan and other parts of Southeast Asia. Items from these locations first made their way to Manila and then on to Mexico. Spices, ivory, gemstones and porcelain were among the goods traded.

Above: Two Jesuit Baluster Vases for the Portuguese Colonial Market, China, 1860-1870. Sold by Michael Backman Ltd to a private collection, US.

The Philippines was ruled by the viceroy of Nueva Espana (as Mexico was then known) on behalf of Spain from 1565 to 1815. In 1565, Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, a Spaniard who had settled in Mexico led an expedition to the Philippines to subjugate the natives. He was made the governor of the new colony and in 1571, he captured a settlement on Luzon which he renamed Manila. Each of Legazpi’s successors was a Mexican. Many of the prominent administrators, soldiers, missionaries, and traders in the Philippines during this period also were born in Mexico. Spain took over direct control of the Philippines in 1815 when the Mexicans started to fight for independence, thus ending 250 years of Mexican rule over the Philippines.

This close connection between the Philippines and Mexico explains why, when there were serious anti-Chinese riots in Manila, resulting in the deaths of many local Chinese, that hundreds of Chinese fled to Mexico (of all places). Many were artisans – silversmiths and so on – and so they resumed their trades in Nueva Espana introducing many Asian techniques there.

Above: Rare Pair of Silver-Gilt Altar Cruets (Vinajeras) with the Emblem of the Franciscan Order, Philippines, 19th century. Sold by Michael Backman Ltd to the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore.

Spain and Portugal became conduits for northern African art influences too. All or part of the Iberian peninsula was ruled by the Moors for around 800 years with Granada, the last Moorish foothold in Spain, falling in 1492 – the same year that the Genoese explorer Christopher Columbus commenced his first voyage to the Americas.

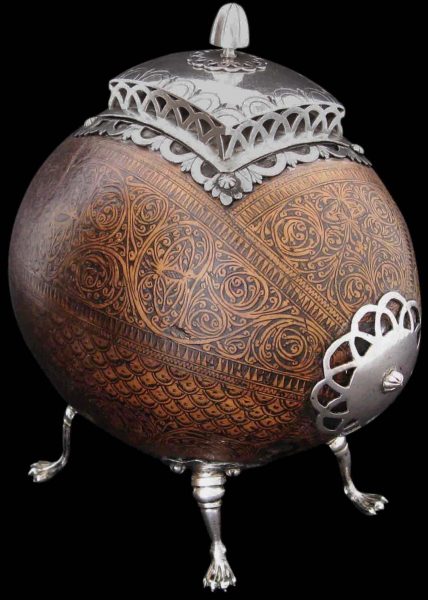

The Moorish occupiers with their Islamic motifs and design elements had a profound and lasting influence on Portuguese and Spanish art. This Iberian-Islamic syncretism was then carried to Mexico, Guatemala and Southeast Asia with Spanish and Portuguese conquest, so that some items from 18th century Mexico for example have motifs that could easily pass for being Indian or Malay. Add on the effects of direct trade between the two regions in the 16th and 17th centuries, migration between the two, and the overlay of a shared experience of Catholicism and these two streams of art and culture – those of the Americas and those of Asia – which seemingly are unrelated can be shown in fact to have significant linkages.

Above: Rare, Finely Carved Coconut Money Box with Silver Mounts (Alcancia), Spanish Colonial Guatemala, 18th century. The motifs used have an Islamic feel, probably on account of North African Islamic influence on the art of Spain.

© Michael Backman

Receive our monthly catalogues of new items by email.

See our entire Catalogue.

Listen to our Podcasts on collecting and other matters.